The Day The Beatles Came to Town

Something New

Posted on August 17, 2015

What was it like when a town was invaded by Beatlemania? Here’s Bill King’s 1985 look at what happened in Atlanta on Aug. 18, 1965, 20 years earlier, when The Beatles played Atlanta Stadium. This article originally was published in Beatlefan #41, August 1985. Also included at the bottom is a 1994 Beatlefan report on a soundboard recording of the Atlanta show that had recently surfaced at that time.

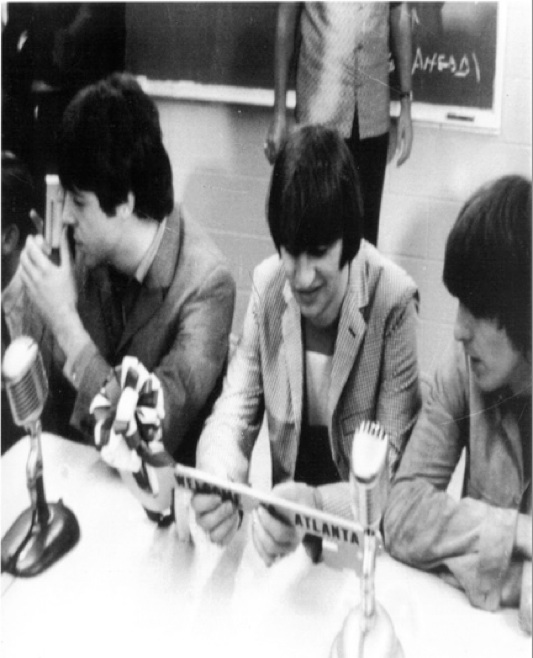

The Beatles with Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen in August 1965.

The Fab Four’s 1965 Visit to Atlanta

Attending last year’s show by The Jacksons at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, Tony Taylor couldn’t help thinking back to another show he’d seen at that same venue.

It was Aug. 18, 1965. Twenty years ago. The day The Beatles came to town.

“There really was no comparison between the Michael Jackson concert and The Beatles at Atlanta Stadium,” maintains Taylor, who as a deejay for WQXI-AM (“Quixie in Dixie”) helped emcee The Beatles’ show.

“The Beatles concert at Atlanta Stadium sticks in my mind as perhaps the greatest event I ever witnessed,” he says. “The entire stadium bordered on hysteria. I can still see the faces of the girls, tears in their eyes, as they hung over the wall and the policemen tried to restrain them. I’ll never forget it.”

Unforgettable. Unbelievable. Words like that are used by members of the crowd of 34,000 who attended The Beatles’ only Atlanta performance.

Even those who weren’t screaming teenagers at the time recall The Beatles’ visit — which preceded the arrival in Atlanta of the Braves — as an epochal event in the emergence of Atlanta as a major city.

“The excitement was shared by the whole community,” says Taylor, now in advertising but at the time the 28-year-old midday man on Quixie, Atlanta’s dominant Top 40 station. “The city took on a different character. The reserved Southerner became a hysterical fan.”

As they’d done around the world, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr sparked unprecedented media coverage, beginning weeks before the show date. As early as July, Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. was quoted by The Atlanta Constitution as saying The Beatles’ visit to Atlanta was causing a stir comparable to the 1939 premiere of “Gone With the Wind” — and in Atlanta, that’s quite a stir.

“The Beatles were a big event, no question about it,” Allen says. “It was a landmark for Atlanta.”

“It was the only time we ever had as much publicity for a show as we thought we should have,” jokes 65-year-old Ralph Bridges, whose Famous Artists firm promoted The Beatles’ Atlanta Stadium concert. “It was fantastic.”

Bridges, who prior to that time had promoted only a handful of rock ‘n’ roll shows, had passed on bringing The Beatles to Atlanta during their 1964 tour because he wasn’t sure he could meet the $12,500 guarantee. A year later, the guarantee for the group was around $50,000. But by then, it was obvious The Beatles’ popularity wasn’t going to fade any time soon, so Bridges took the plunge.

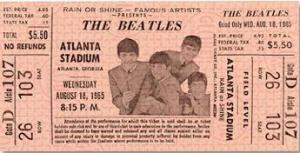

A ticket stub from The Beatles’ Atlanta Stadium concert.

Tickets for the concert at the then virtually new stadium went on sale in May. Lower level seats were priced by Famous Artists at $5.50. Upper level seats (where binoculars were essential) cost $4.50. Response was good, with ticket requests coming from as far away as Guatemala and California. “I was impressed,” Bridges says, “because among the first orders were one from Mayor Allen and one from Bobby Jones [the golfing legend and civic leader], who was buying them for his grandchildren.”

“My 70-year-old mother prompted me,” recalls Mayor Allen, who was 54 at the time. “She insisted I take her to the stadium to hear The Beatles.”

A week before the concert, Famous Artists ran an ad in the papers saying: “Beware of Rumors! We are not sold out. Good tickets still available.” Actually, that meant 8,000 of the upper deck $4.50 seats were available. All the $5.50 tickets were long gone. Because of the size of the stadium, however, it was not a sell-out, with about 2,000 of the 36,000 tickets printed going unsold.

Security — keeping the overenthusiastic fans from harming The Beatles or themselves — was Bridges’ greatest concern. “Superintendent James Mosely of the police department was a big help,” the promoter recalls. “He went with us to the Shea Stadium show in New York. That really scared us to death, because it was within an inch of a full-scale riot. The fans kept coming over the centerfield fence and I thought, ‘Oh, no! How are we going to stop them if that happens in Atlanta?'”

Bridges hired 150 off-duty policemen for the Atlanta Stadium show and, he says, “we prepared a series of lines of defense. It was just like a full-scale battle plan.” Between the crowd and The Beatles would be a waist-high fence, a rolled-wire barricade, a ring of wooden sawhorses and a line of 50 police officers. Insurance for the event cost the promoter $1,900.

Meanwhile, the media coverage had shifted into high gear. WQXI, the “official” Beatles station in town, was featuring regular reports on the progress of their American tour. The “Quixie A-Go-Go” TV show featured The Beatles prominently, and the Saturday before the show, The Atlanta Journal had an interview with Quixie deejay Paul Drew, who’d traveled with the Fab Four and was to join the ’65 tour in New York and travel with it to Atlanta. In a nice bit of overstatement, a photo of Drew in a Beatles wig was captioned: “Paul Drew, The Fifth Beatle.”

A newspaper ad encouraging fans to take the bus to the concert.

Sunday’s paper was full of The Beatles, including tips for parents asking that they not drive directly to the stadium, but let their kids use the special “Beatle Bus” shuttles. There also was a short item noting that “The Beatles in Atlanta: Blight or Blessing?” was the subject of the Rev. Howard Pyle’s sermon that day at Faith Baptist Church.

Wednesday morning, the Constitution’s front page declared that “B Day” had arrived. The Beatles and their entourage of 40 landed at a remote corner of the airport — out of view of fans waiting at the terminal — around 2 p.m. that afternoon on a private Lockheed Electra. Three limousines transported them to the stadium, where they would spend the entirety of their stay in Atlanta.

Janet Caldwell, now a political researcher but then a 31-year-old assistant to Bridges, remembers with amusement that despite all of Famous Artists’ fevered preparations, The Beatles still caught them napping on one item. “Ringo decided to wash his hair,” she says, “and we had to send out, rush, rush, for a hair dryer.”

“My wife Cindy had her stand-up hair dryer brought over from the house,” Bridges says. “That was real unusual in those days. Boys generally didn’t use hair dryers.”

Atlanta caterer Frank Cloudt, who’d been hired to provide The Beatles’ dinner, found them lounging on army cots in one of the stadium dressing rooms that afternoon. Cloudt wanted to know if it was true, as he’d been told, that they wanted hamburgers for their meal. “They said, ‘Oh, no, not again,'” he recalls.

So that evening The Beatles dined on their choice of meats — pork loin, a leg of spring lamb and top sirloin — along with corn on the cob (they had asked Cloudt if he could provide “corn on a stick”), fresh pole beans, fresh fruit, a relish platter and freshly-baked apple pie. A full bar also was provided, though only one Beatle (Cloudt can’t remember which one) had just one drink.

A year later, Cloudt says, when Bridges staged another Beatles show in Memphis, “they told Ralph that the supper they’d had in Atlanta was the best meal they’d ever had anywhere on tour. They enjoyed it.” So much so that they used Cloudt’s magic marker to autograph their four china plates, which Cloudt now keeps in a bank vault. Lennon’s punful plate reads: “Thanks for a flat wear.”

Cloudt, 42 at the time, was not a fan of The Beatles’ music and had approached the assignment with mixed feelings. But after spending some time sitting with the group and talking to them, he says, “I was very impressed. They were well-mannered and easy to talk to. They just seemed like lonely young guys away from home. But they were very accommodating, posing for pictures with groups of VIPs who kept coming in to meet them.”

“They were very easy to get along with,” says Bridges. “Paul in particular. He was taking as many pictures of everyone else as they were of him.”

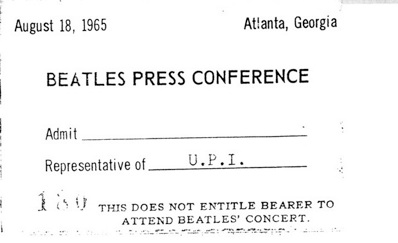

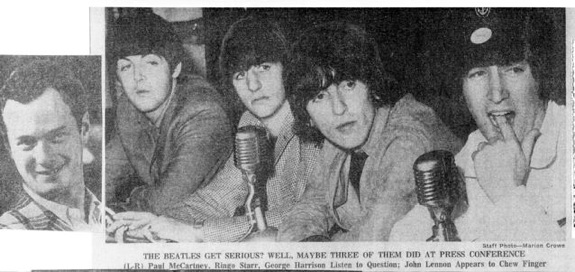

The obligatory Beatles press conference at the stadium — about 15 minutes of mainly nonsensical questions — began shortly after 5 p.m. Around 150 “reporters” were present, many of them from high school newspapers. There also were some members of the local chapter of the Beatles Fan Club, headed by 15-year-old Brenda Jean Bene (now known as “B.J.” and married to WQXI deejay J.J. Jackson), who’d come to present their idols with stuffed animals, rings, jellybeans and other presents.

“I remember they were very nice,” says B.J., who had met The Beatles the year before at the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, thanks to arrangements made by her favorite deejay, Paul Drew. “They didn’t act like big hotdogs,” she says. “John was zany. George was sort of quiet and Ringo was, too. Paul was very gentlemanly and would really take the time to answer your questions.”

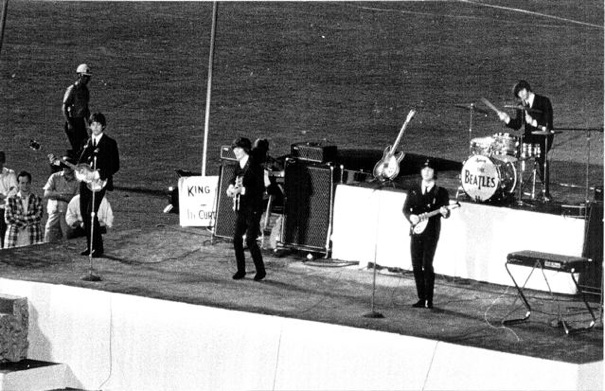

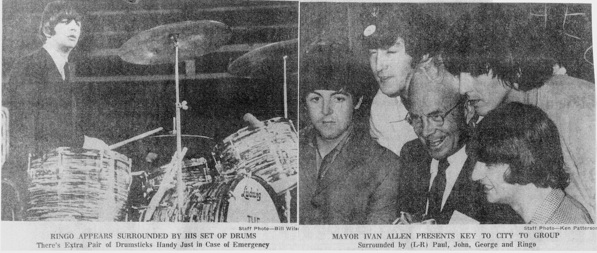

What followed that evening was splashed all over Thursday morning’s front page. Taylor introduced Mayor Allen, who took the stage to declare The Beatles “honorary Atlantans.” Then came the opening acts — King Curtis, the Discotheque Dancers, Cannibal and the Headhunters, Brenda Holloway and Sounds Incorporated.

Taylor, who stood next to The Beatles in the dugout as they waited their turn, recalls that “they looked tired, frightened. But when it came time to go onstage, that feat turned to a smile. It turned into a performance.” Caldwell, on the other hand, recalls, “They seemed to be enjoying the whole thing. They weren’t jaded yet.”

At 9:37 p.m., the crowd erupted into an ear-splitting shriek as The Beatles, clad in dark blue suits, ran from the third base dugout to the stage, situated on second base. “There seemed to be one continuous scream,” Caldwell says. “It was super high-pitched and unrelenting.”

“It was loud,” agrees B.J. “It was really hard to hear them over the screaming.”

The Beatles, however, praised the sound at the Atlanta concert as the best they’d encountered in America. (In those days, touring acts didn’t carry their own sound equipment.)

“I think what really impressed them was that they had enough monitors onstage so they could hear what they were playing,” says Duke Mewborn, president of Baker Audio, which provided the sound system for the show. The company, which generally does sound systems for places like Atlanta Airport rather than concerts, had installed the system for the stadium and so was asked to handle The Beatles’ show. “We gathered every piece of equipment we could beg or borrow,” Mewborn recalls. “We had two large clusters of loud speakers at first base and third base and about 5,000 watts of amplification. But we couldn’t anticipate how loud the crowd really was. It was awesome.”

Still, he says, “their management got in touch later and wanted us to do all their shows. That wasn’t our business, but we did consult on Candlestick Park and a couple of others.”

Inside the stadium, the sights were just as frenetic as the sound was loud. Caldwell remembers that “little girls would throw themselves bodily over the railings onto the rolls of wire and into the arms of the policemen, who would roll them back over.”

The six first-aid stations were kept busy, Bridges says, “mostly with cases of hysteria. I walked around the stadium to see what was going on, and the kids were just continually yelling. I asked a couple of them why they didn’t stop screaming so they could hear the music, and they said they just couldn’t help it.”

Bridges also remembers that, from the stage, the crowd “looked like thousands of fireflies because of all the cameras that were flashing all the time. I thought it was really beautiful.”

The show, covered with four pages of pictures and stories in the Constitution and six pages in the afternoon Atlanta Journal, began with “Twist and Shout.” Then came “She’s a Woman” (during which McCartney’s mike fell over), “I Feel Fine,” “Dizzy Miss Lizzie,” “Ticket to Ride,” “Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby” (Harrison’s only lead vocal), “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Baby’s in Black,” “I Wanna Be Your Man (Starr’s vocal), “A Hard Day’s Night,” “Help!” and “I’m Down.”

“It was a good show,” B.J. recalls. “Better than in Jacksonville. It was perfect weather, unlike Jacksonville, where the winds gave Ringo a hard time.”

Front page coverage in the next day’s edition of The Atlanta Journal.

Press coverage of the concert generally was favorable, if a bit condescending. The Journal said that “hearing one of their concerts is the most amazing and entertaining headache a person can get.”

After the show, the limos took The Beatles directly back to Atlanta Airport, where they eluded a crowd of 200 fans and took off just before midnight for Houston, where their next show was scheduled for 3:30 p.m. the next day.

In articles that ran in the Atlanta papers over the next few days, it was revealed that McCartney had been the heaviest seller at the stadium concession stands, that the state had garnished $5,176 in state income taxes before the show (but expected to refund part of that), and that the show had grossed about $240,000.

“It was the biggest gross we ever had,” says Bridges, whose firm now is mostly a booking agency for acts like Ferrante & Teicher. “But when we got through figuring it up and paying everybody, I think we lost money. Still, we were glad we did it, because we got so much notoriety. It was the biggest thing that ever happened to us.”

And, it might be argued, the biggest thing ever to happen to Atlanta Stadium.

Beatles Atlanta Soundboard Recording Surfaces!

In the fall of 1994, a soundboard tape of The Beatles’ Atlanta Stadium concert surfaced. Here’s Bill King’s report, originally published in Beatlefan #91, November 1994.

A previously uncirculated and (so far) unbootlegged soundboard recording of The Beatles’ Aug. 18, 1965, concert at Atlanta Stadium surfaced recently in Atlanta.

The tape — not to be confused with the bogus concert performance mistakenly passed off by bootleggers as Atlanta in the early ’70s – has slight stereo separation and features emcee Paul Drew’s pre-performance comments (mentioning his travels with The Beatles and plugging a couple of upcoming shows for the same promoter) and his band introduction. Drew, then the top deejay on WQXI (“Quixie in Dixie”), was the city’s “Fifth Beatle”.

The tape has 10 of the 12 songs done that night — “Twist and Shout,” “She’s a Woman,” “I Feel Fine,” “Ticket to Ride,” “Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Baby’s in Black,” “I Wanna Be Your Man,” “Help!” and “I’m Down” — with “Dizzy Miss Lizzie” and “A Hard Day’s Night” missing.

The Beatles’ stage patter on the tape is notable because, while familiar, it includes a couple of comments not previously heard on tapes from the ’65 tour. After “She’s a Woman,” McCartney is addressing the crowd of 34,000 and comments on the sound. (The Beatles said Atlanta had the best sound of the tour because they actually could hear themselves.) “We’d like to carry on now — ooh! It’s loud, isn’t it? Hey? Great!” he says before returning to his introduction of “I Feel Fine.”

After that number, McCartney again thanks the crowd and in the midst of introducing the next number, he asks “Hey, can you all hear me? Can you hear me? [Audience screams] Great, marvelous!” and resumes the introduction with Lennon saying off-mike, “They can all hear, Paul.”

While introducing “Can’t Buy Me Love,” McCartney says: “This next song is one where if you all feel like clappin’ your hands, well, do so, in this one. I’ve been sayin’ this for about three days [the tour had begun Aug. 15 in New York at Shea Stadium] and nobody ever claps ’em, but don’t worry.”

Lennon inserts a Southern cliche into the next intro: “Thank you, folks. You all” and lapses into some of his gibberish before saying the next song is “a slow number and it’s also a waltz, and it’s called ‘Baby’s in Black . . . pool’” in a play on the name of a British resort town.

After “I Wanna Be Your Man,” Lennon kills time before the missing “A Hard Day’s Night,” laughingly saying: “We’ll have to wait a minute now while Paul changes his bass, he’s broken a string! Have you? Whaddya gonna do? Keep talking? What shall I say? [uses phony sincere voice] It’s simply wonderful to be here . . . I can’t think of anythin’ to say so why don’t you just hum and talk to yourselves for a bit.”

Then, after an audible tape splice, Lennon refers to the missing “A Hard Day’s Night” when he introduces “Help!” by saying, “this is also a song from a film we made, and it’s the last film we made.”

The origin of the soundboard recording has not been determined, but the comments and performances match another uncirculated tape in different hands that consists of the beginnings and endings of songs from the Atlanta performance. The two tapes differ in sound quality and slightly in contents: The excerpt tape contains a portion of the missing “Dizzy Miss Lizzie” but ends after “I Wanna Be Your Man.”

The story that accompanied the soundboard tape — that it was made for a reporter from one of the local papers covering the concert — is dismissed as improbable by those familiar with the show. Duke Mewborn of Baker Audio, who handled the sound for the show, said whoever made the tape had to have taken it from their feed. “I don’t remember anybody taping it but that’s not to say someone didn’t ask us for a feed and we gave it to ’em. I just don’t remember it,” he said.

The story surrounding the excerpts tape, which only has one channel of sound, is that it was made at the behest of a local radio station which wanted to use the bits in some sort of promotion.

As we went to press, word already was circulating that one of the underground labels in Italy, where copyright law still allows Beatles concert recordings to be issued legitimately, was planning to issue the soundboard recording of the Atlanta show, paired with the new improved Shea recording that has shown up on a couple of other bootlegs.

(Rick Glover and Glenn Neuwirth contributed to this report.)

Postscript: A speed-corrected and less-hissy bootleg of the tape, “The Beatles Live at Atlanta Stadium, Atlanta, GA 8/18/65” (Toby BBCD 0001), was issued early in 2005 as a limited edition. The version of the Atlanta soundboard recording available on YouTube includes “Dizzy Miss Lizzy” (spliced in from the excerpts tape) but is still missing “A Hard Day’s Night.”

YouTube.com

The Beatles - "Atlanta Stadium" Atlanta, GA. August 18, 1965

by LennMcHarriStarr64

Publicado el 03/06/2012

01. 00:00 "Introduction"

02. 03:02 "Twist and Shout"

03. 04:21 "She's a Woman"

04. 07:36 "I Feel Fine"

05. 10:11 "Dizzy Miss Lizzy" (incomplete)

06. 12:00 "Ticket to Ride"

07. 14:31 "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby"

08. 17:19 "Can't Buy Me Love"

09. 19:52 "Baby's In Black"

10. 22:37 "I Wanna Be Your Man"

11. 25:34 "Help!

12. 28:39 "I'm Down"

Live: Atlanta Stadium

9.37pm, Wednesday 18 August 1965

The Beatles' only visit to Atlanta lasted around 10 hours, but was remarkable for one key reason: monitor speakers on the stage allowed them to hear themselves play - a rarity during the whirlwind of Beatlemania.

The group landed in Atlanta's Hartsfield-Jackson Airport at 2pm, having flown in on a chartered aeroplane from Canada. Although crowds of fans were at the airport to greet them, the plane taxied to a remote area where they discreetly boarded, along with their entourage, three limousines.

The Beatles were taken to the baseball stadium, where a locker room had been designated as their dressing room and headquarters. Some tables and chairs had been assembled in the area, and temporary beds, known locally as 'cots', were also provided. Ringo Starr, amused at the word, climbed into one and sucked his thumb loudly.

The hired caterers offered to make The Beatles hamburgers, but they requested corn on the cob instead. Their meals also included top sirloin, leg of lamb and pork loin, along with the corn, pole beans, fruit and apple pie. The group was so impressed with the quality of the food that they signed the china plates for the caterers.

18 August was a hot day, and as there was no air conditioning in the stadium Paul McCartney requested a large fan for the backstage area, although it made little difference. A number of local VIPs were present, and The Beatles posed for photographs and signed numerous autographs.

Atlanta Stadium - later renamed the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium - had only been recently opened. Tickets for the show had gone on sale two months earlier, with field level seats costing $5.50 and upper level ones $4.50. Fans had begun arriving at the stadium from 4.30am on the morning of the show.

A press conference was held at the stadium from 5pm, and was attended by around 150 reporters.

After the press conference The Beatles were presented with the key to Atlanta by the mayor, Ivan Allen, who proclaimed them honorary citizens.

The stadium doors opened at 6.21pm, and the 34,000 ticket holders began to arrive. Three barrier lines had been erected by police between the stands and the field, and 150 policemen were on hand to keep the fans from charging the stage.

An Atlanta company, Baker Audio, had been hired to supply the sound system for the concert. They brought all their available speakers, which they clustered on the field at first and third base.

John Lennon and George Harrison surveyed the venue from the third base dug-out, un-noticed by fans. They were joined by Neil Aspinall, who told them how to get to the stage for showtime, and where their car would be positioned at the end. Lennon and Harrison then returned backstage where The Beatles changed into matching white shirts and blue suits.

The concert's comperes were Tony Taylor and Paul Drew of WQXI AM. The first act was Brenda Holloway with the King Curtis band, followed by go-go dance troupe The Discotheque Dancers, Cannibal & The Headhunters, and Sounds Incorporated.

The Beatles took to the stage at 9.37pm, running from the dug out as the crowd erupted in screams. They played 12 songs: Twist And Shout, She's A Woman, I Feel Fine, Dizzy Miss Lizzy, Ticket To Ride, Everybody's Trying To Be My Baby, Can't Buy Me Love, Baby's In Black, I Wanna Be Your Man, A Hard Day's Night, Help! and I'm Down.

By 1965 The Beatles had become used to being unable to hear themselves play. FB 'Duke' Mewborn, the boss of Atlanta hi-fi store Baker Audio, decided to give the group something that had never been done before: monitor speakers on the stage, pointing towards the group, to allow them to hear their voices and instruments.

It wasn't just on stage that the sound was different. The state-of-the-art setup on the field included four Altec 1570 amplifiers, each giving 175 watts of sound, which in turn powered two stacks of Altec A7 speakers. Although unremarkable today, in 1965 it was an unheard of amount of power for a pop concert.

The difference was noted from the stage, with Paul McCartney exclaiming after She's A Woman: "It's loud, isn't it? Great!"

Being able to hear themselves enabled The Beatles to play tighter than usual, and they were delighted with the results. Afterwards Brian Epstein suggested that Mewborn deal with the sound for their other shows, but the offer was turned down.

After the concert ended The Beatles sprinted to their waiting limousine. Accompanied by a police escort, they were taken to the airport. The group's aeroplane took off just before midnight, bound for Houston.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario