40 Years Ago: Harry Nilsson and John Lennon Join Forces for ‘Pussy Cats’

by Jeff Giles

August 19, 2014

By all rights, the mid-’70s should have been an easy time for Harry Nilsson. After producing a string of critically acclaimed but commercially middling albums, his star rose in 1971 thanks to a pair of divergent releases: ‘The Point!,’ an animated children’s special and soundtrack, and ‘Nilsson Schmilsson,’ which found producer Richard Perry reining in some of Nilsson’s more esoteric impulses and helping him score the biggest hit of his career.

But while his three-and-a-half-octave vocal range was capable of scaling angelic heights, Nilsson was never all that interested in adhering to pop formula; with ‘Nilsson Schmilsson,’ he toyed with the mainstream the way a bored kitten bats around a ball of yarn, and by the time he and Perry reconvened for ‘Son of Schmilsson’ the following year, he was already chafing under its restrictions. ‘Son’ has its share of commercial moments, but as often as not, Nilsson couldn’t resist the urge to tweak them — usually with off-color humor, as he did by belching in the first few moments of the otherwise lovely ‘Remember (Christmas),’ or by taking a chugging, radio-ready rocker like ‘You’re Breaking My Heart’ and giving its chorus the wholly satisfying (but single-killing) tagline “So f— you.”

If Nilsson’s bosses at RCA were irritated by the relative lack of chart fuel contained in ‘Son of Schmilsson,’ they were downright apoplectic when he decided to follow it up with ‘A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night,’ a collection of pop standards recorded live in the studio with an orchestra. While certainly lovely (and a fine overall example of just what a glorious instrument his voice was in its prime), ‘Touch’ wasn’t at all commercial, and a bewildering departure for fans who’d climbed on board while he was scoring hit singles like ‘Jump Into the Fire‘ or ‘Coconut.’

So it was that by early 1974, Nilsson’s once-promising career seemed in danger of dawdling into the margins. And on top of stalling sales, he had personal problems: his second marriage was falling apart, his new girlfriend was half a world away finishing college in Ireland, and his self-destructive nature — as well as his vast appetite for assorted substances and various means of carousing — had started to affect his creative output. On the PR trail for ‘A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night,’ he joked that his cupboard of material was looking rather bare:

“Most of those songs will be originals, even though I don’t like my songs very much right now,” he winked in a 1973 interview. “I like the songs on the last album, ‘Son of Schmilsson,’ in fact, I love them. But I’m not that happy with the ones for the next album. Still, we’ll do them anyway because I haven’t got anything else to record. They’re just not as good as things I’ve recorded in the past.”

On top of all that, Nilsson needed a producer. After fighting over whether or not the ‘Little Touch of Schmilsson’ project was a good idea, he and Perry parted ways, leaving Harry in need — not that he’d necessarily admit it — of someone who could bring out his artistic best while keeping the level of studio shenanigans to a healthy minimum.

Enter John Lennon.

“There are only four songwriters who can write a line that can really crack you up,” Nilsson told the San Francisco Chronicle‘s Joel Selvin in a 1975 interview. “I consider myself one, along with Randy Newman, John Lennon, and Frank Zappa.”

As with many things Nilsson, it’s hard to know how far his tongue was lodged in his cheek when he made that statement, but there’s no arguing he had good taste in songwriters, and he went back a ways with Lennon; the Beatles were among Nilsson’s earliest and most ardent public supporters. On the other hand, Lennon was by his own admission fairly restless in the studio, and even under the best of circumstances, he probably wouldn’t have been the taskmaster Nilsson needed. Given that early 1974 found Lennon in the midst of his ‘Lost Weekend,’ the ultimate effect was a little like putting two bulls in a china shop. With drugs.

Their collaboration saw its first glimmers in late 1973, when Nilsson paid a visit to the notoriously ill-tempered sessions for Lennon’s Phil Spector-produced ‘Rock and Roll’ sessions. He later recalled that he found “every friend I ever had in my life all in that same room,” as well as Lennon and Spector “in a war.” Rather than being drawn in, he noted, “They were at odds and I think I was a nice little centerpiece they could dance around for a moment. Suddenly, I was the maypole of stability, if you can believe that.” It was at this point that Lennon announced to everyone in attendance that he wanted to produce Nilsson’s next album — not that Nilsson believed him at first.

“When John said, ‘I want to produce you, Harry,’ he didn’t think in a million years that John was going to do it,” suggested Lennon’s assistant and ‘Lost Weekend’ companion, May Pang. “Then he got really nervous.”

But before anyone could get too nervous about making music, there was partying to do. In mid-March, Lennon and Nilsson made headlines when one particularly soused evening ended with the duo being ejected from L.A.’s Troubadour nightclub for heckling the Smothers Brothers. Although Lennon was loudest, Nilsson eagerly encouraged him — and wasn’t really any help when security confronted Lennon at their table.

“All of a sudden his boyhood I’m-being-attacked routine came out. Of course, Harry’s in there, mixing it up as usual, and then they got the bouncers to come and escort the two of them out the door. I’m behind them. There’s like 10 bouncers,” recalled Pang. “John stumbled and he fell on the ground. He was drunk out of his mind by that point. And Harry too. Just wasted. It was just a complete fiasco and I was just so pissed off at Harry for that.”

According to reports published around the time of the incident, while onlookers blamed the escalating violence on Lennon, Nilsson was also singled out for his part in the fracas. “Although Harry Nilsson was not directly involved in the incident, those sitting closest to the Beatle’s table state that it was Nilsson who egged Lennon on, demanding that he get ever more outrageous,” reads a report in the June 1974 Circus. “Apparently both men had been drinking quite a bit.”

“It still haunts me. People think I’m an a–hole and a mean guy. They still think I’m a rowdy bum from the ’70s who happened to get drunk with John Lennon, that’s all,” Nilsson complained in the last interview conducted before his death. “I drank because they did. I just introduced John and Ringo [Starr] to Brandy Alexanders, that was my problem.”

In public, Nilsson may have played the innocent social drinker, but in private, he was already a charter member of L.A.’s hard-living rock crowd — which meant that when he decided to prep for the new album by renting a beach house for himself and the many musicians he’d lined up for the project, wild times were sure to follow. Given that the crowd of players included such notable nightlife enthusiasts as Ringo Starr and Keith Moon, the mood surrounding the sessions devolved from celebratory to senseless abandon.

“We had the wildest assemblage of that part of history in that house,” boasted Nilsson in a 1980 interview with Mix. “It makes the Round Table look like a toadstool.”

According to arranger Perry Botkin, who worked on subsequent Nilsson efforts, that air of barely controlled (or, just as often, uncontrolled) chaos was exactly what Harry was after. “Pretty soon the whole band was bombed and they would get very little work done. That’s the way he wanted it, and that was just sort of one big party; it cost an awful lot of money to make his albums because of that, because of this party going on in the studio.”

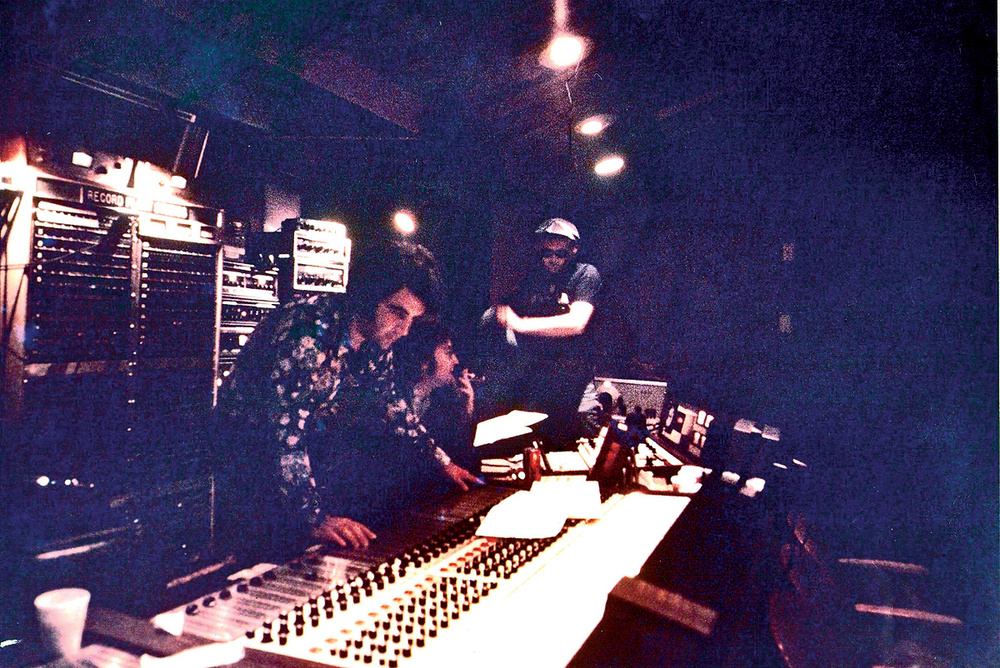

On March 28, six days after moving into the beach house, Nilsson and crew descended upon the Record Plant. They quickly attracted an assortment of famous friends, including Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder, but all that star power failed to amount to much in the way of compelling music; as you know if you’ve listened to the infamous bootleg culled from those early sessions, ‘A Toot and a Snore in ’74,’ to say they were unfocused is putting it mildly.

“It’s murder to listen to,” lamented Nilsson historian Curtis Armstrong. “This was a lot of very talented people wasting their time, blowing off steam. All those great people, what an awful situation.”

These sessions may also mark the spot where Nilsson started suffering throat problems that would continue to dog him throughout recording, eventually forcing Lennon to call the proceedings to a temporary halt. Although the exact hows and whys have always been somewhat hazy — Nilsson blamed it on an infection he picked up after spending the night on the beach — the damage to his vocal cords, and subsequent rapid degradation of his singing ability, is impossible to miss.

“There were lots of recordings from ’73 and early ’74 where his voice was fine,” says Armstrong. “‘Toot and Snore,’ it sounds like it happened there. It may have been the next day, because he sounded worse there than anything.”

Unfortunately for his long-term vocal health, Nilsson insisted on gutting it out, at least partly because he was afraid that if he backed out, he’d never be able to get Lennon back behind the boards. At one point, things got so bad that Nilsson actually hemorrhaged his vocal cords.

“I’m the one who drove him to the hospital and checked him in when they told him he shouldn’t even talk for six months,” Monkees member Micky Dolenz later claimed. “And obviously he wouldn’t hear nothing of it. Polyps, strained vocal cords. Unfortunately, he never fully recovered.”

“John had suggested — because he was in such bad shape — you gotta get your throat taken care of,” Pang insisted. “At night he’d be snorting and drinking, so what good would that be? He didn’t tell John he was losing his voice. He didn’t tell him he was hemorrhaging in his throat, he didn’t say it was bleeding. He’d say it was just sore.”

Nilsson did, however, seek medical attention on more than one occasion, undergoing acupuncture and enlisting a group of cohorts that included graphic artist, musician, and producer Klaus Voormann to lend moral support during a visit to the doctor. “The doctor said sternly to Nilsson, ‘You are not going to talk for two weeks. And you are not going to sing. If you have anything to say, write it down,’” Voormann remembered. “Of course, Nilsson didn’t keep to that, at least not for long.”

Finally, Pang recalled, “He sounded so horrible. … Harry would do one thing to make his vocals great or get his voice back, and at night he’d be out there drinking again, and it would undo everything. And this was a cycle. Finally John said, ‘We can’t do it here. We’ll have to redo all the vocals back in New York. I can’t be in L.A. any longer.’”

“In L.A. you either have to be down at the beach or you become part of that never-ending show business party circuit,” explained Lennon. “That scene makes me nervous, and when I get nervous I have to have a drink and when I drink I get aggressive. So I prefer to stay in New York.”

“I think it was psychosomatic,” shrugged Lennon later. “I think he was nervous because I was producing him. You know he was an old Beatle fan … But I was committed to the thing, the band was there and the guy had no voice, so we made the best of it.”

On April 10, Lennon halted the sessions in L.A., decamping to New York for another round of recordings that, by all accounts, was far more businesslike than the first. But the closer they got to finishing the new album, the clearer it became that Nilsson’s relationship with RCA Records had degraded to the point that the label’s new president was dragging out the signing of Harry’s new contract, a healthy $5 million deal hammered out in the wake of the ‘Schmilsson’ hits. Understandably annoyed on behalf of his friend, Lennon marched down to the label’s excecutive offices with Harry in tow, scoring Nilsson one last round of financial security along the way.

“John said, ‘Look, it’s about Harry. You know, you’ve only ever had two artists on your label: Elvis [Presley] and Harry. He told me what you’re paying him. Look, for that money, I’ll sign it. You’ve got an artist! Pay the two dollars!” “Pay the two dollars’ was like saying, pay the parking ticket, rather than fight City Hall. He said, ‘I’ll sign with you, for that kind of money,’” Nilsson recalled Lennon saying. “When the guy heard that, his mind went ‘Bing!’ Dollar signs! So he said, ‘Well, we’ll have to get the contracts together.’ I said, ‘No, no. They’re on the 10th floor. They’re in Legal. Ask Dick Etlinger, in Business Affairs. He’s the guy.’ So he calls up and says, ‘Do you have the Nilsson contract? Could you bring it up here?’ Because he didn’t want to look like an a–hole in front of John. … John made me $5 million that minute. I looked at John for a minute and I almost cried.”

With contract in hand, Nilsson and Lennon put the finishing touches on the album, but they still weren’t finished butting heads with RCA; their original title for the record, ‘Strange Pussies,’ was sternly rejected (something Nilsson would face again a couple of years later, when he wanted to name an album ‘God’s Greatest Hits’). Settling on the more innocent-sounding ‘Pussy Cats,’ they still managed to get one last jab in on the album cover, putting a rug between a pair of alphabet blocks reading ‘D’ and ‘S.’ It’s a silly joke — but then, more than a few critics and fans thought the album was, too.

‘Pussy Cats’ was a divisive record, and it isn’t hard to hear why. Not only is Nilsson’s voice obviously in rough shape, but the music is loose; the whole record sounds a little unsteady, like the songs are barely being held together and the entire thing could collapse at any moment. In fact, at a few points, it actually sounds like the wreckage after a collapse — in ‘Old Forgotten Soldier,’ for instance, Nilsson’s vocals are little more than a husky haze wafting through haunted wreckage. To listeners still holding out hope for another ‘Without You,’ it had to be disconcerting.

For those who can hear it without the baggage of Nilsson’s pristine earlier work attached, however, ‘Pussy Cats’ is an album rich with its own rewards. Forced to work without the amazingly elastic voice that had always been his calling card — he later jokingly referred to his upper range as having been “donated to whiskey” — he responded with some of his most heartfelt vocal performances, including his spine-tingling wail on ‘Many Rivers to Cross‘ and the raspy melancholy of ‘Don’t Forget Me.’

And if a few songs wobble into inessential territory — covers of ‘Loop de Loop’ and ‘Save the Last Dance for Me,’ for example, were hardly necessary — others pack enough of a buzz to give a contact high 40 years after the fact. Nilsson and Lennon’s take on Bob Dylan‘s ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues‘ stands as a sort of wild-eyed companion piece to ‘Jump Into the Fire,’ while ‘All My Life,’ with its seasick strings and lyrics lamenting the “bad times” spent “Shooting’em up / Drinking ‘em up, taking them pills / Fooling around,” lays bare the weary self-awareness that ballasted Nilsson’s hedonistic flights.

Still, it’s easy to understand why ‘Pussy Cats’ was greeted with bewilderment, indifference and derision after it arrived in stores on Aug. 19, 1974. Mustering a chart peak of No. 60 — a steep comedown from the No. 3 showing enjoyed by ‘Nilsson Schmilsson’ — it effectively ended Nilsson’s run as a commercial force. He’d release four more albums for RCA, and the last one — 1977′s ‘Knnillssonn’ — was the biggest seller of the bunch, peaking at No. 108.

The label didn’t do a lot to promote those later efforts, but then, Nilsson had a knack for putting a fly in the ointment. ‘Son of Schmilsson’ and ‘Pussy Cats’ found him indulging in bursts of off-color humor, but it became a hallmark of his subsequent efforts, which included songs such as ‘Jesus Christ You’re Tall,’ ‘How to Write a Song,’ and the bathroom stall-worthy ‘She Sits Down on Me.’ None of it was exactly surprising coming from the guy who used a group of nursing home residents as backing vocalists for the ‘Son of Schmilsson’ track ‘I’d Rather Be Dead,’ but still — when it seemed like he ought to be straightening out and doubling down, Harry often appeared to be shrugging.

All of which is not to say that those albums are without their charms, or that Nilsson wasn’t capable of channeling heartbreaking beauty in his later years. (Quite the contrary: ‘Knnillssonn’ is arguably his most consistent — and loveliest — work.) “He could go into the studio with a matchbook with a few words on and he could come out with an amazing contrement of music and lyrics,” recalled his friend and collaborator Van Dyke Parks. “There was a pragmatic nature to his intoxication. He wasn’t just a sybarite. He was a driven man — there was, at all times, a sense of urgency and purpose.”

Publicist Derek Taylor, a longtime Beatles associate and the producer of ‘A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night,’ pleaded a similar case in his liner notes for the original ‘Pussy Cats’ pressing. “Harry and John … have been living a vampire turntable recently but have sucked no blood except each other’s and not so much of that,” he quipped. “Anyway, the cross-transfusion works, so what the hell.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario