Philip Norman on George Martin: ‘It could easily have been Lennon, McCartney and Martin’

The acclaimed Beatles biographer recalls his encounters with the studio genius who helped the band achieve ‘delirium in sound’

Philip Norman

Saturday 12 March 2016

I first met George Martin in 1979, when I began researching my Beatles biography, Shout!. Friends and journalistic colleagues had done their best to talk me out of the project. “You’re wasting your time,” they said. “Everyone knows everything about the Beatles that there is to know.” Indeed, at the start I positively shrank from mentioning the B-word, claiming merely to be writing about popular culture in the 1960s. How different from today, when the appetite for Fab Four trivia seems inexhaustible; if I proposed a book of Ringo’s collected laundry lists, publishers would form a queue.

Martin by then was long past his Beatle-producing days – with him, unlike them, there were no lasting scars – and had become a recording mogul with his independent AIR studios in London and on the Caribbean island of Montserrat. Even his famously straight and suave persona had become a bit rock’n’roll at the edges, the suits giving way to cardigans, the Brylcreem to sideburns, the elegant voice letting out an occasional “fuck”. But the overall impression was still (to quote the Beatles’ first manager, Brian Epstein) that of “a stern but fair-minded schoolmaster”. What a schoolmaster, what pupils – and what results!

There was, of course, much to tell about the Beatles which was new and of which Martin, their indispensable collaborator for seven years, had often been the only other witness. That first interview, in his modest west London maisonette, produced one revelation after another. He told me, for instance, how he’d unwittingly caused the sacking of the band’s original drummer, Pete Best, on the eve of their fame, and Best’s replacement by Ringo Starr. Martin never demanded that Best be dropped from the lineup, only that a more adept session drummer should play on their records. But the others jumped at the chance to ditch a member whose face – and hair – had never really fitted.

He told me about the memorable night at Abbey Road studios in 1967 when John Lennon’s bleak masterpiece, A Day in the Life, was recorded for the Sgt Pepper’s album. For the song’s two instrumental breaks, Lennon, with characteristic vagueness, asked Martin to provide “a sound building up from nothing to the end of the world”. To achieve this, Martin hired a 41-piece symphony orchestra who performed in full evening dress embellished by clowns’ red noses and fake gorilla-paws handed out by the Beatles. There was no written score: Martin simply gave the musicians a top and bottom note and told them: “Gentlemen, in between, it’s every man for himself.” As a result, a producer who never so much as puffed a joint created veritable drug-delirium in sound.

He was no scandalmonger, yet our first conversation indirectly lent weight to a startling idea: that Brian Epstein’s death in 1967, which spelled the beginning of the end for the Beatles, might have been no accident, as the inquest found, but murder. The honest but naive Brian couldn’t control the fortunes that fell into his hands through his precious “boys”, and totally botched a Beatle-merchandising operation that might have given the world, among other things, motor scooters with saddles like Beatle wigs. So much money was lost in America that one bankrupted plastic-guitar manufacturer reportedly took out a contract on him. Martin recalled “sinister moments” on early American tours when the band’s minders, apparently recruited straight from the mob, spoke casually of “taking care of people”.

The tributes paid to him this week have placed insufficient stress on his extraordinary honesty. In the music business of the early 1960s, producers whose artists wrote original songs customarily took a share of their publishing royalties and, often, a share of the composer credit. Morris Levy, the thuggish boss of America’s Roulette label, died the owner of dozens of song-copyrights despite not having written a line or note of them. With a less scrupulous producer, John and Paul’s work might easily have borne the credit “Lennon-McCartney-Martin”, or the Beatles could have been made to record songs written by Martin as B-sides or album tracks. But he practised none of the scams open to him – indeed, sought no reward but the satisfaction of turning raw talent into polished hits.

After the Beatles’ breakthrough, a string of other Liverpool acts, managed by Epstein and produced by Martin – Gerry and the Pacemakers, Cilla Black, Billy J Kramer and the Dakotas – also enjoyed huge international success. In 1963 Martin had a UK No 1 single for 37 weeks out of 52, yet was still on his EMI salary of £3,000 a year. To add insult to injury, a recent minor pay-rise disqualified him from that year’s staff Christmas bonus.

When I began John Lennon: the Life in 2004, I asked Martin for a further interview. As it happened, my house in north London was a couple of hundred yards from his AIR company’s studios in a converted church. “Oh, all right, come along,” he said, “but I don’t know what else I can tell you.” He told me about the shiver that ran down his back the first time he heard Lennon’s lonely unaccompanied voice sing, “I heard the news today, oh boy…” About the two versions of Strawberry Fields Forever, a soft, lyrical one and a hard rock one that he fused seamlessly together after Lennon couldn’t decide between them.

He told me about the fist fight between Lennon and George Harrison during the fractious Let It Be sessions, which had been completely hushed up at the time. About making the Abbey Road album while Yoko Ono lay on a bed in the middle of the studio. About Lennon’s dissatisfaction with even the most brilliant of his tracks and his ambition – expressed just before his death – to get back with his old producer and do the whole lot again. “What, even Strawberry Fields, John?’ Martin queried. “Especially Strawberry Fields,” said John.

After that, we would occasionally meet on Beatles memorial occasions such as the 2012 reissue of the Yellow Submarine cartoon film (an undervalued gem, which Martin scored in addition to producing its Beatles tracks). He was a man who enjoyed a joke, the older the better, like his own about Gerry Marsden’s three UK No 1s in a row: “I always call it my Gerry ’at trick.”

Among the other guests that night were the Conservative peer and Times columnist Danny Finkelstein, a hardcore Beatles fanatic. I mentioned I’d once had an hour’s conversation with the not-yet chancellor, George Osborne, exclusively about the band. “I gave George his first copy of the Revolver album,” Finkelstein said. “Now everyone wishes it had been a real one,” I replied. Sir George cracked up at that.

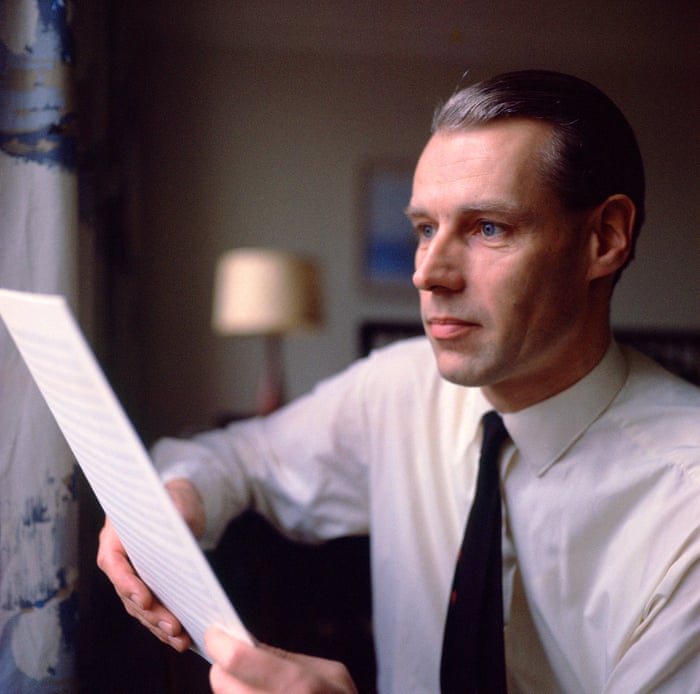

‘Scrupulously honest’: George Martin in 1965.

Photograph: David Magnusr/Rex/Shuttestock

When I began researching my [forthcoming] Paul McCartney biography, I asked for yet another interview. Martin worked with McCartney for years after the Beatles’ breakup, in essentially the same role: turning the ideas of an instinctive musical genius into reality. “Oh, all right,” the courteously exasperated message came back yet again. “But I don’t know what I can possibly tell you that’s new.”

This time I went down to see him at his home in rural Wiltshire, taking a bottle of superior claret by way of apology. I think it was the last interview he ever gave. He seemed unchanged, but for the device like a tiny amplifier on the sofa arm which betrayed his cruel hearing loss. And in yet another wonderful hour he had much else to tell me about working with Paul that was brand new.

Paul McCartney: The Biography by Philip Norman is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on 5 May, £25.

Click here to buy a copy for £20

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario