Yoko Ono: 'I thought my music was beautiful all along'

She was subjected to decades of vilification. Now everyone from Gaga to Sparks are lining up to pay tribute. How does the 83-year-old artist feel about the world catching up to the Yoko Ono sound?

Alexis Petridis

Monday, 22 February 2016

‘I won’t stop’ … Yoko Ono at MoMA, New York. Photograph: Richard Perry/New York Times / Redux / eyevine

oko Ono is giving me a demonstration of her vocal technique. Almost half a century after it was first unleashed on an unsuspecting British public – at a 1968 Ornette Coleman concert at the Royal Albert Hall, while John Lennon was away in India with the Maharishi – it’s still a hair-raising experience, particularly when it’s happening a few feet away from your face. In fact, it’s all the more so because the demonstration is interspersed with Ono’s explanation of how she came upon her unique approach to vocals, and Yoko Ono’s speaking voice is incredibly soft and delicate – not adjectives anyone is ever going to apply to her singing.

It all started when she was a little girl, she says: her family were wealthy, they had maids, “and my mother said: ‘Don’t you ever go to the servants’ rooms, it’s very bad, because they’re talking about things you don’t want to know.’ And sure enough, I just sneaked up and listened to it. And these two teenage girls, they were combing their hair and talking. ‘My aunt had a baby yesterday.’ ‘Oh, really?’ ‘Yes, and she was making noises.’”

At this point Yoko Ono emits a series of frankly terrifying grunts and wails. “And I just thought: ‘Oh my god, a woman does that when she has a baby?’ There was a totally sanitised image about a woman, you know, they were supposed to be just pretty and make pretty noises. Nobody tells you they go...” – more grunts and wails – “You know? So I was scared, and I sneaked back to my room, but that really stayed with me. And years later, I started to create all sorts of sounds.

“Just last year, I was invited to Beijing to do an exhibition and at the opening, I did a little sort of … not a concert, but I said: ‘OK, I’m going to do something in a woman’s voice, you know, and I…” – more screams and grunts – “and they couldn’t believe it! But that’s what it is. I mean,” she smiles sweetly, “don’t you think that we would have maximum expression when we have a baby? The baby is the human race.”

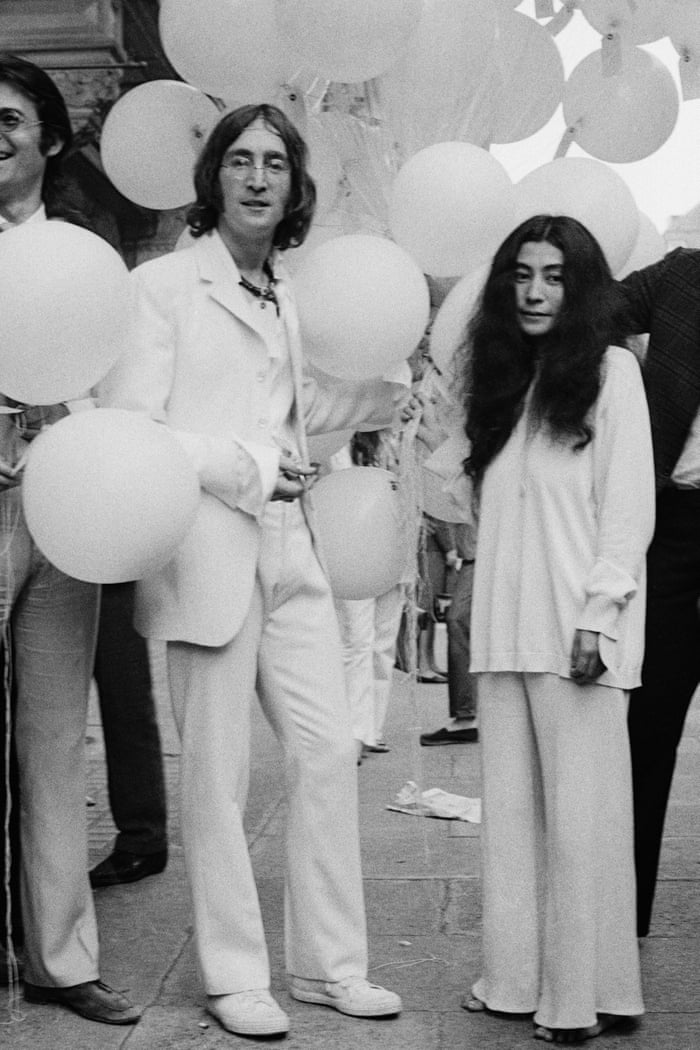

John Lennon and Yoko Ono launch an exhibition of his artwork in London, 1968. Photograph: Andrew Maclear/Getty Images

It’s not just the disparity between her speaking voice and her singing that make Yoko Ono in person seem an intriguing study in contrasts. A lot of what she says is impressively bullish, with the screw-you confrontationalism of the early 60s avant-garde art world where she first made her name: “I don’t accommodate the audience,” she says flatly at one point. “I ask the audience to accommodate.”

Equally, by her own admission, she chooses her words with a degree of caution, which is presumably the result of having spent the 35 years since Lennon’s death having her every pronouncement picked over for any shred of evidence of an ongoing feud with Paul McCartney. “If I say something, I can forget it, but it just keeps growing in itself. So I have to be careful what I say. But if someone took me differently from what I thought I was saying, well, that’s their problem, really.”

She is funny, smart, entertaining, possessed of an extremely twinkly laugh and very handy with an aphorism – “Life is like a suitcase, you can squeeze a lot in” – but there’s no mistaking a certain steeliness about her. If you ask a question she’s not keen on, she gives you a hard stare, then blithely ignores what you’ve just said and answers as if you’ve asked something completely different. Lest anyone think age has mellowed her, one story she tells about making a recent album concludes with her rounding on the musicians and demanding: “How dare you tell me what to do?”

Then again, a certain steeliness is probably just as well. Today, she seems keen not to dwell on the bleaker aspects of her life, other than to note that “the thing that really made me survive is to create something, to totally immerse myself in it, because that’s a situation I’m so familiar with, and that makes me get on with things”, but nevertheless, you’d be hard pushed to call Ono’s life anything other than turbulent. She’s variously been reduced to begging for food in the aftermath of the second world war; committed to a psychiatric hospital after trying to kill herself; had her eight-year-old daughter abducted by her second husband and raised in a succession of dubious-sounding religious cults [Ono and her daughter Kyoko eventually met again in 1998, after 27 years]; been subjected to decades of public vilification rich with misogyny and racism – even today her name is still a popular jokey metaphor for a controlling spouse – and seen her third husband murdered in front of her.

And yet, here she is, 83 years old, in seemingly fine fettle – behind the sunglasses she keeps perched on the end of her nose, her face looks eerily unchanged from the one you see in the last photos of her and Lennon together – in London to collect a gong for being an inspiration at a music awards and promote Yes, I’m A Witch Too, a second volume of collaborations and remixes of her work on which everyone from Sparks to Moby lines up to pay tribute. She says she loves having her work reinterpreted or remixed, partly because it fits in with an idea she had decades ago: “The first albums I made with John, Two Virgins and Life With the Lions, we called them Unfinished Music, and I think that idea has developed into something: you have a certain artistic attempt and then you openly involve other people.”

Both the award and the album are evidence of the way Ono’s reputation as a musician has undergone a vast reassessment. The music she made with Lennon on 1970’s Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band and 1971’s Fly is often brilliant, inspired and genuinely innovative, the result, she says of not really having any understanding of rock music – “I didn’t think I am I going to get to number one on the chart or something because I didn’t even know what a chart was” – and trying to apply “the incredible, intense sounds” she’d heard in modern classical music or free jazz to the format: alternately hypnotic and disturbing, Mind Train or Why bear comparison with the celebrated avant-garde krautrock of Can or Faust.

Yoko and John in New York, 1980, the year he was murdered. Photograph: David McGough/Life Picture Collection/Getty

Even when she started writing more conventional songs, an intriguing idiosyncrasy showed through. Her contributions to 1980’s Double Fantasy are noticeably edgier and more in tune with the new wave era than anything Lennon came up with for the album: Walking On Thin Ice, the song they completed on the day he was murdered, was even more striking, a claustrophobic piece of experimental punk-funk with uncannily prescient lyrics about loss. “It’s so eerie, I mean, I thought of all that before John’s death, and I didn’t know he was going to die, and supposedly John didn’t either, so that happened in a very intricate and strange way.”

But for years, her music was, at best, viewed as a mammoth indulgence on the part of her husband, or at worst greeted with derision and anger: “In the beginning I didn’t understand it, but then I said: ‘Maybe that’s the reaction because people aren’t used to it.’ It didn’t disturb me because, luckily, I came from a totally different musical background: my father was a classical pianist, into Schoenberg and twelve-tone, very strict, there was no way you could satisfy him because his musical standard was so high.”

Lennon was always hugely supportive, she says. He loved making music with her, not least because he knew the results couldn’t be compared to the Beatles. “I’m sure the other Beatles had the same problem: they’d made it very big, but then out of that, what would they do? Ringo went into films, things like that.” And for the rest of his life, Lennon remained steadfastly convinced that others would come round to the results: “He was a very special person, he had very high expectations, he understood that the world is going to change.”

Yoko Ono performing with her Plastic Ono Band in 2010. Photograph: Lester Cohen/WireImage

She says she isn’t sure when he was eventually proved right – “It’s my arrogance, but I thought it was beautiful all along” – but in recent years, she’s been lauded as an influence by everyone from Sonic Youth to Lady Gaga. Her own albums, usually made with her son Sean, hammer away at rock’s avant garde fringes: 2013’s Take Me To the Land of Hell was as challenging as ever. She fits music in between her career as an activist and a conceptual artist: last year she had a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. No, she says, she’s not considering retiring: “I won’t stop. No, I never think that. Artists are obsessive, they want to keep doing it. And I’m an artist. My sole interest is in creating something beautiful.”

Perhaps recalling the earlier demonstration of her vocal technique, she adds a quick qualifier: “When I say beautiful … well, the maximum beauty can be ugly to some people.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario