www.austinchronicle.com

Denny Laine Saves the World

British Invasion pioneer played it, sang it, saw it all

BY RAOUL HERNANDEZ

THU. APR. 26, 2018

Two weeks ago, Denny Laine (born Brian Frederick Hines) entered the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame with the Moody Blues, whose 1964 UK chart-topper “Go Now” features his lead vocal. The British guitarist, 73, also holds the distinction of being the only constant member of Wings alongside Paul & Linda McCartney. He appears at the Cactus Cafe on Sunday.

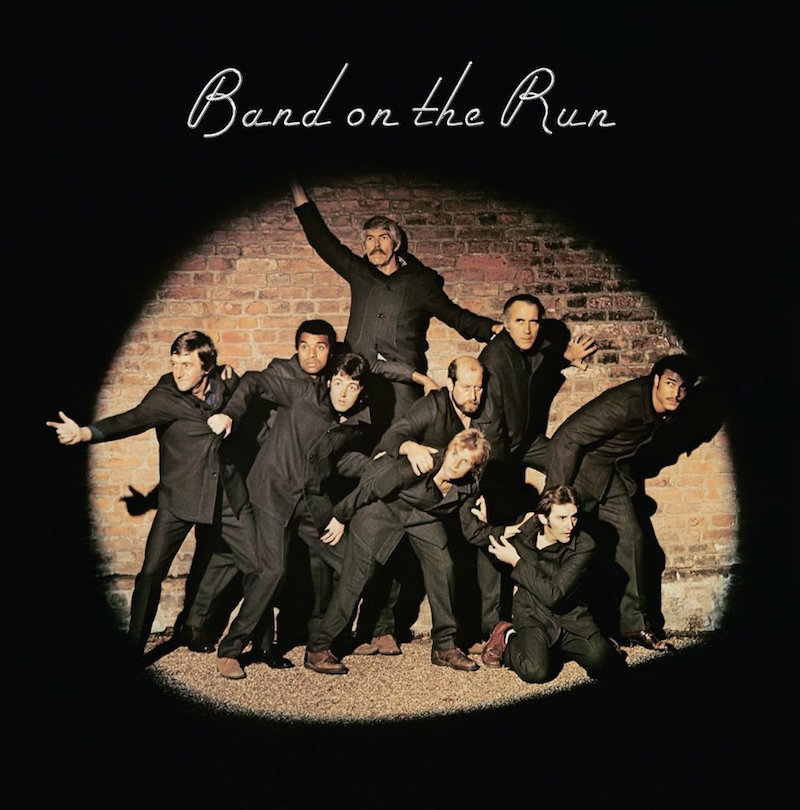

Freeze, sucker: (l-r) Michael Parkinson, Kenny Lynch, Paul McCartney, James Coburn, Clement Freud, Linda McCartney, Christopher Lee, Denny Laine, John Conteh

Austin Chronicle: You’re from Birmingham, which for some in the music realm remains infamous as the birthplace of Black Sabbath and Judas Priest. What’s your experience of Birmingham?

Denny Laine: Well, not only those groups, but the Spencer Davis Group, and the Moody Blues, and the Move, and UB40.

AC: All great bands.

DL: Well, yeah, it was the Moody Blues and Spencer Davis Group that came down from Birmingham originally. Birmingham was not the place you could get a record deal. There was no music scene in Birmingham, really. It was just factories that had workers from all over the world. So a lot of musical influences came through Birmingham – reggae, Irish show bands. Most of the Birmingham bands were into pop, but you had to move to London to get a deal.

AC: Was Birmingham a place people wanted to escape from or just that London was where it was happening?

DL: Well, both. I joined the Moody Blues because they wanted to go to Germany first. Two of the guys had been out there working in the same clubs as the Beatles. Then we got discovered in a blues club. The Moody Blues were a blues band, so when we got discovered, we were taken to London. That’s where we started to make it. That’s where the record labels were. That’s where the action was.

When we started getting popular, a lot of bands came from Birmingham. Brum Beat was a magazine from Birmingham that started to bring music to the forefront, so therefore Birmingham became a music scene after that. More of an original music scene, let’s say.

Wherever people in the British Commonwealth came from to work in the factories after the war, they brought their music with them. Like I said, there was reggae and all sorts of styles we were influenced by, but especially American music thanks to American Forces Network in Germany. And Radio Luxembourg! We used to listen to all that American music. That’s how we first latched onto it.

AC: Had it not been for World War II, would the English have heard the blues and American R&B like they did?

DL: Definitely not, because if it weren’t for the war and the American Forces being in Germany, we wouldn’t have had a radio station playing R&B. We weren’t picking up on blues music at first. We were picking up on American pop music, but that led us to investigate, like kids do now. They research past music. Listening to American music, we got into blues before the American public did. We were very interested in it, and also there wasn’t the same sort of prejudice and separation between black and white music in England, or France. Europe was open to it all. The Moody Blues was very big in France, because they liked that we were basically playing blues.

We started out a little bit like bands in London – the Yardbirds, Eric Clapton, all those people. Jeff Beck. We were all into the blues. The Moody Blues and the Spencer Davis Group were the only blues bands that came from Birmingham to London and started being a part of that scene. So we were listening to old blues and eventually got a hit with “Go Now,” which is basically a gospel style song. We started to go more into the R&B scene, getting some obscure records we could learn and put in our set.

When I left the Moodies, Justin [Hayward] and John [Lodge] came along, and they had to do different music. That’s when they began writing their own stuff, because I was more into the blues side of things and they weren’t. They weren’t schooled in that. Fortunately for them, they did their own thing and it was very successful. I’m very happy about that. I’m glad they went on to bigger and better things. It gave me a sense of closure and I was happy for them.

AC: Were you surprised to hear “Nights in White Satin” after leaving the group?

DL: No. It’s a great song. Justin’s a great songwriter. And the treatment of “Nights in White Satin” was very much the Moody Blues sound, which was a lot of voices and flutes and mellotrons. Even though we didn’t use mellotrons when I was in the band, we were very much keyboard-based.

AC: Was your family musical?

DL: Yes, because after the war, everybody was into music in some sense. They were playing their own music. During the war, you had to make your own entertainment, all right? Practically every family, just to cheer themselves up, would sing and play music. My sisters and my brother were all very much into music. A couple of them were dancers.

My brother had a ukulele. That’s how I started. I found a ukulele in the cupboard. He was in the navy for 10 years, so I didn’t really grow up around him. I grew up around my sisters’ influences, all the different styles of music they were into. And then my parents had an act that they used to sing together in the local club.

I was put into a theater school called Jack Cooper School of Dancing where my sisters had gone. From there, I got into playing guitar in between the two halves of a musical, for example. I would get up there with a piano player and do some of my own stuff at the intermission. And then it developed from that into me getting into a band while I was at school. So it was definitely a musical influence from my family that got me going.

But it wasn’t just that. I was into gypsy jazz. I was into classical music. I was into all sorts of music as a kid. I was very curious about ethnic music and different styles. I loved Django Reinhardt. I loved Ella Fitzgerald. I was also influenced by all the crooners of the day, like Johnny Ray, Frankie Lane. Sinatra. That was family music. To play the guitar, I listened to that music, not so much pop music. When Buddy Holly and Elvis came along, I got into that more.

AC: So the British Invasion and that generation of musicians came out of an auto-entertainment movement born of the bunker?

DL: That’s exactly what it was. It’s pretty obvious if you think about it. They’re all waiting to be bombed in the shelters in the backyard, so they’re making music to keep themselves cheered up. It was a way of carrying on. Of course, after the war, it made its way to the young kids – because I was born nine months before the war ended – as a way of making a living. Everybody was encouraged to. I was never told by my parents, “Oh get a real job.” They were happy for me to do it. It was a lot of energy from all the kids. That’s why there were so many bands.

In school, I was in a couple of bands and then I went on to having my own band. It got quite big. In fact, the drummer from ELO, Bev Bevan, was in that band with me. It was called Denny Laine & the Diplomats. We got quite big in Birmingham, but the fact is they didn’t want to turn professional at the time. That’s why I joined the Moody Blues. We were all ambitious. We wanted to be famous. We wanted to make some money. We wanted to do something we enjoyed doing and we were encouraged to do it. I don’t know whether that’s the case these days.

I think these days, kids are encouraged to do it because they can see the history of the music business. In those days, nobody knew what the hell they were doing business wise. That’s why everybody got ripped off. Managers and record companies were useless except for distribution, but they didn’t have all the other stuff together. They didn’t know what to do with music, rock bands and stuff. We were all part of that Renaissance.

I don’t see many people from the past now because I live in America, but I got so friendly with everyone we used to play with, people like the Yardbirds, Rod Stewart. The Stones. We knew all these people. As young kids, we ended up being on the same labels. Not labels necessarily, but agencies. That’s where we got the Beatles tour and went with Brian Epstein [as a manager] at their recommendation. We got friendly with the Beatles because of that. I got friendly with Paul [McCartney] and that’s how I ended up working with him. I knew him for all those years before. It seems like years, but it wasn’t. You did a hell of a lot in two years. It was a lot more concentrated. That’s how it all came together, really.

AC: You’re talking about the birth of the modern music industry, of course, so how much did that change your life when “Go Now” went to No. 1 in the UK?

DL: We were on the Chuck Berry tour at the time and guess who was in the opening band? Opening the tour was Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce. They were in the opening band, the Graham Bond Organization, so I became friendly with them through that tour. As “Go Now” hit the bottom of the charts, it started creeping up because with every different city on that tour, people would see us playing it live and go buy it. That tour definitely helped promote it. That’s what you had to do in them days. You have to do it now. It’s come full circle. You can’t make money in the music business unless you play live now.

AC: Revenue is derived from touring.

DL: That’s exactly right. Back then, we didn’t have any money because management had it all. We didn’t know where it went, but we didn’t have any. Look at all the bands that happened to. The worst case of all is Badfinger. It effected all these bands that broke up and committed suicide. All sorts of things happened because people didn’t see the money.

AC: Did you see a single penny from the success of “Go Now”?

DL: No, not to start with. All we had was that we were looked after. Things were paid for by management, but nobody had any personal money. When we chased after it, somehow management vanished. Recently, the last couple of years, thanks to Steven Van Zandt, we did a settlement and the rights to our old recordings reverted back to us, so we now see some money. And that’s because Steven Van Zandt wanted to use “Go Now” in a film he was making, so after investigating ownership, it seemed the rights had reverted back to us. We found out that we actually did own all that stuff. It took 40 years, but we got some money back.

AC: Were you surprised when the Moodies were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame?

DL: I wasn’t surprised. I thought it should have been years ago, not necessarily with me, but just as the band that they are now. I thought they deserved to be in because of their popularity. In some ways, if I hadn’t left, they wouldn’t have got so popular. I did them a favor in some ways [laughs]. I still respect all those guys. We had some great fun in the old days, so it’s great we’re being inducted together.

Originally they weren’t going to ask me to be inducted, and then I got the call saying I was inducted. The rumor went around that I wasn’t going to be and then I was, but it had nothing to do with the band. They wanted me to be. It’s all worked out well in the end and I’m very pleased for them. I’m pleased for myself, of course, but I’m pleased for the band. By their body of work they deserved to be in there a hell of a lot earlier. It’s not fair, you know?

AC: What are your feelings on a body like the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame?

DL: I think it’s great there’s a Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. That’s the first thing. How it’s run, I don’t know much about that. There’s a team that gets together and votes. I know, for example, Steve Van Zandt and Pete Asher and [deejay] Cousin Brucie and various other people wanted me in. They voted for me to be in it. They wouldn’t have voted for the Moody Blues if I wasn’t in it. They helped me.

AC: Does Wings deserve to be in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame?

DL: No, because Wings was never a band. I’m sorry, it wasn’t. It was a Paul McCartney project. You have to know that. We were known as Paul McCartney & Wings, but we weren’t actually a band. We weren’t like the Moody Blues, all equal members. It was Paul’s band. That’s the end of it. Although I stuck around for all those years, it wasn’t a group. In the public eye it was, but in business, we weren’t. It was the Paul McCartney project. That’s why he got inducted as an individual artist. Wings is part of his induction, separately to the Beatles, actually.

AC: Interesting to hear you say that because Wings was such a hugely popular group. All 23 singles the band released hit the Top 40, and Wings had five consecutive No. 1 albums in the U.S. Those are big numbers. And the group had a definitive life to it, right? It’s a decade, ’71-’81, so I’m surprised to hear you say it wasn’t a group, but rather “the Paul McCartney project.”

DL: Well, it was 99 percent Paul’s material. He wrote most of the stuff. I was around the longest of all the members, but it’s still Paul who had the popularity from the Beatles, of course. I had a little bit from the Moodies, but not that much. It was him guiding the ship, so that’s it. It was his popularity and his music that made it popular. My contribution was that I knew Paul so well. We got on so well together and had the same influences musically. We were good in that sense. We had a natural working relationship that was easy. I wasn’t in awe of Paul like a lot of people were. He was just a mate. I knew him.

The Beatles were a band. I wasn’t a big Beatles fan, although I obviously appreciated their talent. I was not a fan, though. I was in a band. The Moodies were rivals to the Beatles – in a friendly way. They’d come by our house and play us their new record and we’d play them our new record. We were friends, but still rivals. We always were. I don’t look at it like being a fan, then. I look at it as me working with Paul because he’s a fellow musician and we all grew up together. Our working relationship was very easy because of that.

AC: Was the experience of being in Wings one of living in a Beatles-eque bubble of fame?

DL: In many ways of that, I was on the outside looking in. Although the Moody Blues received some of that, it was nothing like the height that the Beatles got to, or the fame that they got to, so I was watching a lot of that going on, and I was impressed in some ways, but in some ways it was a bit scary. As Graeme [Edge] from the Moody Blues will tell you, one of the reasons they didn’t put their pictures on their album covers was because they didn’t want to be that famous. It’s too dangerous. Although a lot of bands want to be successful, when fame comes along, they start wishing they weren’t. It’s all that craziness that goes along with being famous. It distracts from the music, but at the same time, it presses you to keep coming up with something new. It’s a double-edged sword, let’s put it that way. It was a great experience, for sure.

Also, you’ve got to remember, to the Moodies, theaters were the biggest venues we ever did. The Beatles only did a few stadium things in the early days, but Wings was all stadium. It started out in small ways. To get the band good, we did a university tour just purely to practice in front of an audience without too much exposure and without too much attention put on us. It was stadiums all the way after that. Big arenas. Big.

AC: Must have been a surreal bubble when you, Paul, and Linda ended up in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1973 to record Band on the Run.

DL: That was just because the other two guys didn’t want to go. I know why they didn’t want to go. I was never told. Nobody said anything to me. They just didn’t turn up, so we went anyway because we already got the studio booked. Ginger Baker lived out there. We only worked with him on one track. We worked at the nearby studios and he knew all the people out there. It was kind of nice to have somebody living there that we knew. He introduced us to everyone. It was because of music that we went out there, to get different influences, like African drumming. We went there for that reason and we were influenced by it.

The studio wasn’t that great. We did have [Beatles engineer] Geoff Emerick visit, but we didn’t need a lot of equipment. Paul played drums, I played guitar, and we got the songs that way. Paul got robbed a few nights before we arrived and all the cassettes we had of the rehearsals, the band rehearsals for the “Band on the Run” song, were stolen. We had to start from scratch and memory. So he got on the drums, we counted four, and got to the end of it. Each song. And then we overdubbed all the rest.

AC: I find it extraordinary that just the two of you made Band on the Run, because it’s such a rich album, and one that’s certainly stood the test of time.

DL: I know. You have to give some credit to Linda, even though she doesn’t get enough. She gets a lot of negative stuff, but she was part of that Wings vocal sound. Even Michael Jackson said that to Paul: “Hey, I love the harmonies. Who’s doing the harmonies?” And Paul goes, “Me, Denny, and Linda.” That sound we had was because of her voice. She wasn’t experienced, but we got her into it and it did give a sort of sound to the stuff. You can’t mock that.

AC: On the succeeding Wings at the Speed of Sound, you’ve got two songs on there, “The Note You Never Wrote” and “Time to Hide.” What can you tell me about those songs?

DL: “Time to Hide” is my song, but “The Note You Never Wrote” is not my song. It’s Paul’s. I just sang it. He wrote it with me in mind. If you think about it, it’s the same tempo as “Go Now,” a 3/4. He was a big fan of “Go Now” and the Moody Blues. When we were on tour with the Beatles, he was always at the side of the stage watching us, taking notes or whatever. He loved “Go Now.” He liked us because we had our own sound. He was always trying to get us to do certain songs.

You know what Paul’s like: He’s always selling his songs to somebody. He wanted us to do the thing that Mary Hopkin had a hit with, “Those Were the Days.” He didn’t write it, but I think he had the rights to it. He thought that would be a good single for us and we said no, “It’s not our style, really,” but he thought it was and it probably would have been a big hit for us if we’d done it. So he got Mary Hopkin to do it and he produced her doing it.

With the Moodies, he was always checking us out and because we were all writers too. That was fascinating to the Beatles. They were influenced very much by the Beach Boys and Everly Brothers, of course, harmony-wise. They were also influenced by the Moody Blues in those days. Again, we had our own sound. Donovan even did the sleeve notes on the first Moody album. We were part of a little group of people that all admired each other.

AC: Your name is also on one of the best-selling singles of all time in England, 1977’s “Mull of Kintyre.”

DL: Well, I co-wrote that one. I did write that with Paul, although I still consider that to be his song because he came up with the chorus. When I heard the chorus, I said, “That’s a hit song.” So the next day we went out and wrote the rest of it. He only had the chorus. “Mull of Kintyre” was the biggest single of all time up until “Don’t They Know It’s Christmas” by that big charity.

AC: Band Aid.

DL: Yeah, yeah. “Mull of Kintyre” was huge for [Wings]. It became a Christmas song because it came out near Christmas. We were very much in the public eye during that Christmas, on television a lot, so it was a huge seller. Still to this day I do that song. I do the songs you mentioned off of Wings at the Speed of Sound. I do all that stuff within my set.

AC: Had you not taken a backseat to Paul in Wings, would you have been leading your own version of something like the Moodies?

DL: Yeah, in some ways, but there again, I wanted to work with Paul because I knew him and I knew it would be fun. I knew eventually we’d do well. In all ways. But yeah, I did give up. I had a solo career going for about a year with a thing called the Electric String Band, where I had two cellos, two violins, and a little power folk-rock trio. Paul and John [Lennon] and Peter Asher saw me close the first half of the show I did with Jimi Hendrix at the Saville Theater in London. That was Brian Epstein’s theater. Ash saw me do that show and that’s one of the reasons Paul called me a few months down the line. He saw me doing something a little bit different.

Once I got the call from Paul, it was great fun to start something new, but I did end up being there for a long time and in some ways neglected my own career. I did put a couple of albums out and then eventually, well you know what happened to Paul in Japan. [McCartney was arrested at the Tokyo airport in 1980 when eight ounces of marijuana were found in his luggage.] I did work on the last two albums, Tug of War and Pipes of Peace, but they weren’t Wings albums. That’s when I thought, “Now’s the time to try and do my own thing again,” which is what I did. Nobody fell out. We just weren’t going to be going on the road for awhile. That was it.

AC: Do you still talk to Paul?

DL: Through the office, but not really. The last time I saw him was a few years ago. We went to see UB40 in London together and we wound up spending the night watching them, reminiscing a bit. Again, we didn’t fall out. I don’t think he was too pleased about the fact that I wanted to leave, but I was at that point where I thought I was frustrated, so I wanted to go out and do my own thing.

AC: I was surprised to discover that one of your children counts Peter Grant as their grandfather. Is that right?

DL: Yes, my youngest daughter is his granddaughter.

AC: So much has been written about Peter Grant. Is he really the gangster that everyone makes him out to be?

DL: No, because Peter started out as a wrestler. He was in the business as a bouncer, a security guy who ended up being given the job [of manager]. Look, Don Arden, people like that, they’re all a little bit like that. I don’t know about the word “gangster.” I wouldn’t give him that title. He used to drive people about. He was like a personal assistant to a lot of people, and that’s the job he had with the Yardbirds. He was sent out on tour with them as their security guy.

When the Yardbirds turned into Led Zeppelin, Peter became their manager. So he became their manager by default, but he had the strength of character to deal with all that. He was tough, but his heart was for the band. It really was. He was the fifth member of the band. They trusted him and he never ripped them off. He loved them. Therefore, he became a great manager because of that – because he wasn’t trying to rip them off and they trusted him.

My experience was the same. I got very close to him in the end and was at his funeral and everything. I’d split up with his daughter by then. And I knew Peter before I got involved with his daughter. John Bonham was a big friend of mine. I also knew Jimmy Page quite well in the early days. And John Paul Jones. I worked with John Paul Jones in the studio. He did the string parts for a song of mine called “Say You Don’t Mind” that Colin Blunstone [of the Zombies] had a hit with. So I knew those guys.

John Bonham used to come and watch us in my band Denny Laine & the Diplomats. He’d come to watch Bev Bevan the drummer. He was a fan. That’s how I got to know Johnny. All during the Led Zeppelin time, Johnny and I were friends. He even came on tour with Wings once, just jumped on the plane and came with us. Johnny and I were big friends.

AC: You’ve lived such a rock & roll life. Why do you suppose this music, above all genres, holds such a sway on people? What is it about rock & roll that’s bigger than classical music and jazz and blues and hip-hop?

DL: Well, it’s because it came from all those things you just mentioned. It came from jazz. It came from the blues. It came from people we used to admire in the Thirties, Forties, and Fifties. It came from that and we took it to another level by basically being white. We had a bigger audience. There was not so much prejudice [in England]. Elvis wouldn’t have been so big if he hadn’t have been white. You get what I mean? We’re so influenced by black artists. We all are. We owe everything we do to black artists. Rap for example. Chuck Berry was doing rap. Muddy Waters was doing rap.

AC: Louis Jordan.

DL: Yeah, it’s all rap. It’s all rap. Everything is embodied in that music.

AC: Civilization is in such dire straits right now. Can something like rock & roll save the world?

DL: It pretty much has already. I mean in general. Music is like food. You can’t live without it. When there’s problems in the world, you write about it. Look at the blues artists. They were down and out, and they wrote about their lives. Look at country music. You’re writing on behalf of the people. It’s not necessarily your own personal stuff you’re writing about. Some of your personal stuff, but your songs are based on everybody’s experiences. Music soothes people, let’s be honest. Dancing and creativity, anything like that gives people hope. It’s like a religion and it’s somewhat based on religion. After all, a lot of that music came from the church. Gospel hymns, the Bible. It all came from that.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario