www.harpersbazaar.com

THE BALLAD OF SEAN & YOKO

She was blamed for breaking up the Beatles, then the world mourned with her when John Lennon was killed. Now, at 84, Yoko Ono is finally being recognized for her artistic legacy—with a little help from her son, Sean.

By Stephen Mooallem

Jul 31, 2017

Sean Lennon is talking about his mother’s child-rearing philosophy. “She had a very sort of postmodern, post-hippie, post-feminist way of thinking,” he says of Yoko Ono.“ It was very liberal, and she always treated me like an individual. She never really told me not to do anything, except get a Mohawk or a tattoo. So there were very few boundaries. She believed that kids are individuals and shouldn’t be treated like a subservient class.”

At 84, Ono—singer, artist, activist, and guardian of the legacy of her late husband (and Sean’s father), John Lennon—is enjoying a remarkable late-career reappraisal. The Ono oeuvre, once maligned as a conglomeration of unbearable neo-Dadaist pranks and unlistenable music, is now considered haute. Her conceptual-art projects—films, installations, happenings, and performance pieces, such as her 1964 work Cut Piece, in which she invited viewers to cutoff swaths of her clothing with a pair of scissors—today are seen as groundbreaking. Her albums and recordings, which mostly eschewed melody and traditional song structure, are held up as revolutionary. Even her clipped aphoristic “instructions,” famously compiled in books like her seminal 1964 Grapefruit, have been heralded as presciently tweet-like. And two years ago, New York’s Museum of Modern Art explored some of Ono’s early efforts in the exhibition “One Woman Show, 1960–1971.” (Back in 1971, the only way she could get an exhibition at MoMA was to invent a fake one, along with a fake ad campaign, that she publicized in local papers featuring an image of her standing in front of the building holding an oversize “F.” The fictional show was called the“Museum of Modern [F]art.”)

"We’d gone through the loss of my father together, so I witnessed her struggle."

But while it took the wider world decades to truly appreciate Ono as an artist, Sean, now 41, began to do so early in life. “I don’t really know when I realized, ‘Oh, Mum does performance art or she is an avant-garde artist, and Dad was in a band called the Beatles.’ I just remember realizing when Dad passed away that his music really touched a lot of people,” he recalls. After John Lennon was shot and killed outside the Dakota, the family’s apartment building on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, in December 1980, “people suddenly started gathering outside,” says Sean, who was five years old when his father died. “For months, they were living in [Central Park], and singing ‘Give Peace a Chance’ and Beatles songs. So my sense of people’s connection to the music probably started around then,” he says.“ But my mother’s music was the music I really grew up with. I wasn’t thinking about whether it was mainstream or not. When she made Season of Glass”—written in the wake of John’s death and featuring an image of his blood-spattered glasses on the cover—“it impressed upon me the idea of what art and songwriting is. We’d gone through the loss of my father together, so I witnessed her struggle, and then I saw her turn that struggle into art literally within a few months. I realized that art was a way of processing and understanding your experience.”

Yoko Ono with her son, Sean Lennon, in 2015.

KEVIN MAZUR/GETTY IMAGES.

Ono and Lennon first met at London’s Indica Gallery in November 1966. At the time, he was married, and the Beatles had just released Revolver. Nevertheless, the pair quickly merged their personal and creative lives in a way that was at the time and to their disappointment—frequently misunderstood.

Case in point: Early on in the couple’s relationship, in June 1968, they planned to

plant a pair of acorns on the grounds of Coventry Cathedral as part of a late entry

in a sculpture exhibition. The site where the acorns were to be buried was surrounded by a circular white bench from which visitors could sit and watch the acorns grow. The bench had a plaque that read, yoko by john lennon, john by yoko ono. According to Ono, the installation was Lennon’s idea, meant both to symbolize their coming together and—like many of the projects they would initiate—to promote world peace. Unfortunately, the bench was moved to another area of the property because the show’s organizers quibbled with the notion that what Ono and Lennon submitted was, in fact, art. Lennon went so far as to write an impassioned letter to Canon Stephen Verney, who had been in charge of overseeing the exhibition, to protest the decision, but to no avail. Lennon eventually sent his driver to retrieve the bench.

The episode was indicative of how many of their collaborations would be received: gestures borne of love and idealism were often met with cynicism and confusion, and frequently resulted in anger directed at Ono, who was blamed—wrongly—for leading Lennon astray. The difficult run of albums that Ono and Lennon made together, including the recently reissued Unfinished Music No.1: Two Virgins (1968), Unfinished Music No. 2: Life With the Lions (1969), and Yoko Ono Plastic Ono Band (1970), shockingly un-Beatles-esque as they were, seemed to only deepen the animus. In many ways, they were taken as a bitter affront on the part of Lennon—a repudiation of his life with his mop-topped bandmates and the mass adoration that had been showered upon them. “You hear a lot of things on those records,” Sean says. “You hear a couple in love and having fun and experimenting and indulging in their sort of honeymoon. Then, on the other hand, you can’t help but think of how that impacted their relationship in the future because of a lot of people’s negative responses. Obviously some people loved what they were doing together, but there was a lot of mainstream negativity, and I think that was hurtful.

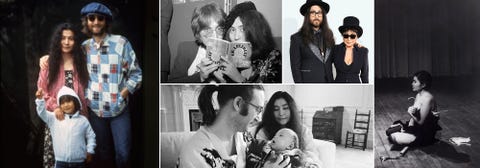

From clockwise left: Ono with husband John Lennon and Sean in Japan in 1979; Lennon and Ono at a Grapefruit book signing in London 1971; mother and son at the Grammy Awards, 2014; Ono performing Cut Piece in New York, 1965; the family at home at the Dakota; 1975

From clockwise left: Nishi F. Saimaru © Yoko Ono; Steve Granitz/WireImage; Central Press/Getty Images; Lynn Goldsmith/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images; Minoru Niizuma © Yoko Ono

Ono’s response to the antipathy has always been to practice a kind of "psychic jujitsu," says Sean. “When people have asked her how she has dealt with all this hate that’s been focused on her since she met my dad and the bad press and the mis-understandings and the blaming of her for things that were outside of her control, I have heard her say, ‘Well, it’s all just energy.’ I do think in a way that she does thrive off of energy—whether it’s good or bad—and she manages to somehow refocus that impulse into something positive.

And though John Lennon died nearly four decades ago, Sean’s recollections of their time together are vivid. “There was this movie that my dad watched with me called La Planète Sauvage,” he says. “It’s a French sci-fi cartoon from 1973, and it’s still one of my favorite films. After he passed away, I watched it all the time. My dad and I used to play this game where he would scribble something nonsensical on a piece of paper,” Sean adds, “and I would have to turn it into something by drawing on it. Then we’d trade, and I would do a scribble, and he would turn it into something. That game was monumental for me; if I hang out with a kid, I’ll still play it. And a lot of the stuff that I’ll draw is kind of alien landscapes from La Planète Sauvage.”

As for Ono, she remains too out of this world to be fashionable. But to say that she has finally been acknowledged is an understatement. She has been embraced as a sort of éminence grise of the avant-garde. And in June, it was announced that she’ll receive a songwriting credit for Lennon’s 1971 hit single “Imagine,” in accordance with his wishes.

“I don’t really know where my mom got her rebellious nature from, but she obviously has it in spades,” Sean says. “She just does what she feels; she doesn’t belabor anything or second-guess herself. From a very early age, she was doing completely radical work.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2017 issue of Harper's Bazaar.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario