www.theguardian.com

Back with the real Beatles: the White Album reviewed - archive, 1968

Fifty years ago, the Guardian printed two reviews of The Beatles and recommended listening to ‘what is likely to be the biggest event of the pop music year’ in stereo

Geoffrey Cannon

Fri 9 Nov 2018

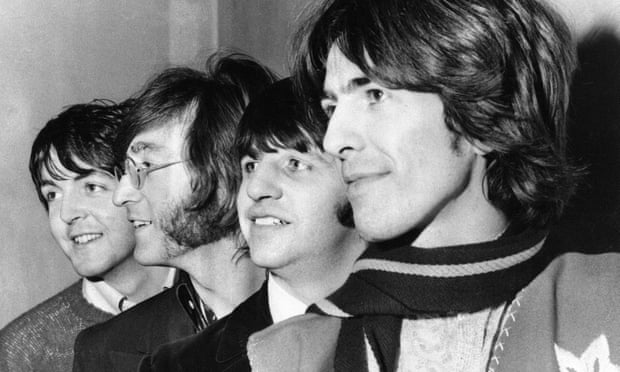

The Beatles, February 1968. Photograph: AP

Back with the real Beatles

19 November 1968

The Beatles have accustomed us to look for clues to the meaning of their work. Everyone can look at the cover design of Sergeant Pepper and play “spot the reference.” There’s Stan Laurel and Max Miller; Marlon Brando and Dylan Thomas; but who’s that peering over the top of Paul McCartney’s head?

So, we are encouraged to think, the Beatles are influenced by all these figures. Then: perhaps the reverse. Do we see a gallery of heroes or villains? Or, worse still, a mixture? Or perhaps Peter Blake the designer made his own choice? Since there is no way of deciding between these questions this, interpretative, approach to the Beatles’ work is clear victim of a put-on. Nevertheless the questions go on and on.

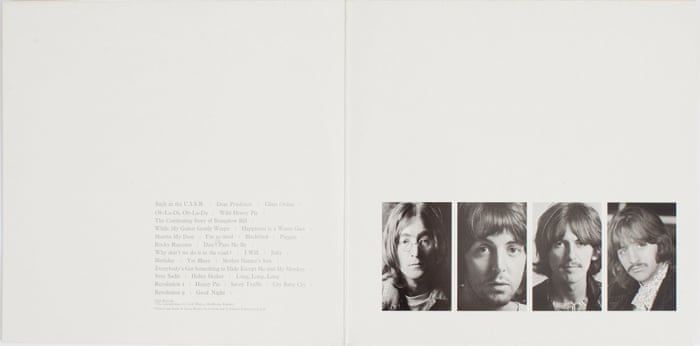

Now, look at the cover of The Beatles. Outside, it’s blank white gloss card, with The Beatles blind embossed, plus a serial number (mine’s 0010192, what’s yours?). Inside, a list of the tracks, and black and white photographs of each member of the band, looking quite unlike each other. Tucked in with the discs, the same photographs, loose, in colour. For your bedroom wall. Also a big foldout: one side the lyrics; the other side, a soft-core Richard Hamilton collage of the Fab Four’s history.

The panorama of Sergeant Pepper’s cover design is on the acetate of The Beatles. Most of the tracks on the new album are packed with sounds in the style of other musicians. Back Home in the USSR [sic], to take the first track, contains Chuck Berry (Back Home in the USA), the Beach Boys (409 and California Girls – the last a direct quote), and early Beatles. A full list for all 30 tracks on the album would be of around 60 names.

What is the meaning of this? There are several interpretations. Perhaps the Beatles are quoting musicians they admire. Or, on the other hand, perhaps those they fear – “we can do their thing, better.” Perhaps they have turned their backs on the world (this will be a popular view) and can now only play games. Or perhaps the album is a self-conscious tour de force, parallel to the Holles Street Hospital chapter in Ulysses.

And then, apart from use of other musicians’ sounds: the “mystery” tracks. Is Julia “really” about John’s mother? Is Sexy Sadie the Maharishi? Is Martha My Dear Paul’s dog?

Nope, Or, yeah. As John sings in Glass Onion: “Well, here’s another clue for you all/The walrus was Paul” (yeah). Since their public beginnings, the Beatles have, instinctively and obsessively, and with style, attempted to outdistance interpretation. Their obsession has entered their work since Rubber Soul, their first self-conscious album, has dictated the form of The Beatles.

Inside shot of the Beatles’ White album. Photograph: Alicia Canter for the Guardian

If the Beatles’ opacity in the face of interpretation – of attempts to view their work in terms of reference to the external world – were merely a matter of a quarrel with the press, then neither it nor The Beatles album would be worth considered attention. In fact both are a demand to be seen as artists, and to refuse the rule of journalists or commentators. And the Beatles’ instinct has served them well; their stand is crucial to them, to our grasp of their music, and afterwards to our own self-perception. Does this sound like a gigantic claim? So it is. It’s difficult living among heroes, to avoid a flip tone of voice. But the Beatles are not camp stars; they are, whether you, I or they like it or not, the real thing. Their stature is meaningful and can be delineated.

The Beatles rates high not just as new music, nor just as art, but as a demonstration of a fact so blatant as to be invisible, so close and new that we’ve few bearings on it yet: that art is now in process of replacing science as the determinant of the way we see ourselves and the world. The point has to be made in this context; without it the potency of the Beatles, now fully equalled only by Dylan and Godard, remains hermetic; an enigma.

But the Beatles’ artistic consciousness is autonomous. It cannot be felt or discussed except in its own terms. The joyful idea contained in the Beatles’ music is that individual consciousness can be as real as the external world. They are the first full citizens of the post-scientific age, with a few other artists. The Beatles are their music; who John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo are at home is another matter.

Still from The Beatles’ performance of Hey Jude on David Frost in 1968. Photograph: The Beatles

Back to spring

26 November 1968

“Earth, water, fire, and air met together in a garden fair,” chants Robin Williamson, of the Incredible String Band, in Koeeoaddi There. And if the four elements were to band together, what then would remain impossible?

Hot from Hamburg six years ago, laying their raw rock on us, the Beatles were all fire and air, with the temperament that folk medicine puts with these elements: ardent and articulate. Do you remember the unequivocal exhilaration of She Loves You? Its rhythms had a depth and sex new to white rock. Eldridge Cleaver, a Black Panther writing from the especial ghetto of prison in Soul On Ice, saw what was happening, “The effect of these potent, erotic rhythms is electric … The Beatles are offering up as their gift the Negro’s Body, and in so doing establish a rhythmic communication between the listener’s own Mind and Body.”

To everything there is a season. The Beatles have run full cycle, in their new double album, back to spring again. “Can you take me back where I came from, can you take me back?” Paul McCartney asks at the beginning of Revolution 9. Yes, to the beginning of a new season. Authentic progression in music does not consist in plucking up roots.

Earth and water have met with fire and air in The Beatles. (PCS 7067/8 is the stereo number: and the album is worth changing to stereo for; it transforms Helter Skelter, for example, from a nifty fast number to one of my best 30 tracks of all time.) Associating the Beatles with the four elements, and the four humours, is more than a whimsy conceit.

George Harrison has seen the truth, and is anxious that we should see our truth. He’s a preacher, man of fire. When his songs speak of “you,” the address is direct. He achieves his character in While my guitar gently weeps, which, with Phil Ochs’s Tape from California, is the first track I know that succeeds in making magnanimous love serious and touching.

Pete Best, the original Beatles’ drummer, was bound to be sacked. The base needed a man of earth and phlegm. And having Ringo sing Good Night over George Martin’s schmaltz festival makes it right: the straight man’s dream.

Paul McCartney is the storyteller of the band; and he shows, on this album, that there’s no such thing as a paradigm McCartney number. Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da, Blackbird, Helter Skelter, and Honey Pie are all perfect, professional songs, packed with exact quotes and characterisation. His songs are the most copied, because he’s not concerned to project his own, no doubt ravelled, self into what he writes. His “you” is objective; he’s building fun-palaces, not monuments. Doubts don’t affect him, he’s the sanguine man, and his car is marvellous.

“But when you talk about destruction don’t you know that you can count me out …in” is a paradigm John Lennon line (Revolution 1). Or, again, “I am he as you are he as you are me” (I am the Walrus). And Lennon’s music is now like that, too, as hard for him to make as for us to hear. Water is the element of instability; and Lennon’s melancholy in Julia and Revolution 9 is too steeped and self-pitiless for him to attempt fluent musical solutions. He’s the closest to our times, and the most impressive man of the four.

To contrast the Beatles, polarising them in terms of their four tempers, only serves to demonstrate their rich range together. Although The Beatles has several hints of separation, it’s what they share that makes the album great. And The Beatles is our new spring. There’s no way verbally to capture such music. It’s the sound that counts.

The Guardian, 19 November 1968.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario