George Harrison wrote the Beatles song "Savoy Truffle" about Eric Clapton's chocolate addiction. "Savoy Truffle" is a song on The Beatles' "White Album." The song mentions a variety of different chocolate candies that Eric Clapton loved eating, and, subsequently caused Clapton to get a lot of cavities.(www.sploofus.com)

www.popmatters.com

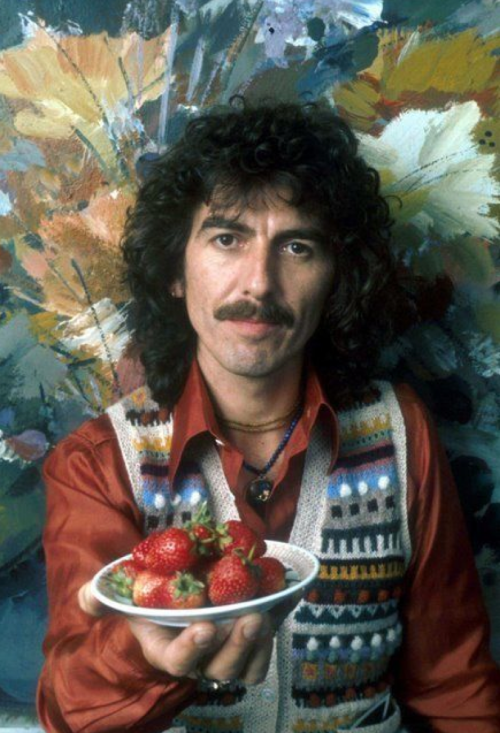

George Harrison's "Savoy Truffle"

Holiday Reflections on Sweets and the Beatles

BY MEGAN VOLPERT

5 December 2016

TRUFFLES PHOTO FROM HEALTHSEEKERSKITCHEN.COM

If you ask those who know me pretty well, they will tell you my favorite Beatle was John Lennon. This is incorrect. My wife will tell you true: it’s George Harrison. Lennon is widely credited as the band’s conscience in the face of Paul McCartney’s more instinctively capitalist pop music impulses, and this is just one more way that Harrison’s songwriting contributions have been disregarded over the years. His post-Beatlemania solo work was often criticized for its preachiness, but if one goes back to his Beatles material, Harrison never pretended to be more pop star than preacher.

There was a great tribute paid to his entire body of work in 2014, the George Fest charity concert organized by his son, Dhani Harrison. A standout track toward the end of the first disc is “Savoy Truffle”, which I confess to not having heard before. It’s one of the deeper cuts from the Beatles catalogue, not completely obscure but hardly Top 40 material. As the holiday spirit takes over and I begin to devote many minutes to consideration of pies, eggnogs and sweets generally, I feel myself turning toward “Savoy Truffle” as the best possible type of wintry instruction.

Harrison wrote the song as a cautionary reminder to his pal, Eric Clapton. Clapton apparently has a massive sweet tooth. The refrain, focused on tooth decay, is “you’ll have to have them all pulled out / after the Savoy truffle”. But for Harrison, as a burgeoning practitioner of Eastern spirituality assembled a la carte, tooth decay was unquestionably a symptom of a deeper moral decay.

The chorus is an examination of the cumulative effects of candy consumption, which highlights a clearly incrementalist approach to indulgence that wards off hedonism. One piece of candy doesn’t do much damage, and the benefit seems to outweigh the cost. At some point, however, one gives in to eating the whole box. At that point, satisfaction is minimal, reaching for the next candy is a compulsive behavior, and a stack of tiny decisions has accumulated into an ultimate lack of judgment that now has to be managed as a painful crisis. Any holiday dieting listicle with tips on how to manage your winter weight will tell you as much, that one bite is happier than 40 bites and you’ve got to take life one bite at a time.

“You know that what you eat you are”, reminds Harrison at the beginning of the second to last verse. He actually consumes most of the candy in the box one line at a time. This is a very specific candy: the Good News box from Mackintosh. Alas, it’s not available anymore, except in song. In the course of the first two verses, Harrison drew heavily from the titles and descriptions of the specific candies in this box. “Creme tangerine and Montelimar / A ginger sling with a pineapple heart / A coffee dessert” and “Cool cherry cream, nice apple tart / […] Coconut fudge”. It’s worth noting that Montelimar also rhymes with the apple tart. Instead of building a couplet out of that, however, Harrison used this as the end of the first line in two different verses. This calls attention to the fact that rhymes of the first two verses are entirely interchangeable: Montelimar / heart / news and tart / apart / blues.

That’s not simple cleverness; it makes the same argument that’s made by the surrealism of the listing of candies. Namely, that all candy is candy—there’s no specialness, no “there” there. Does one really have strong opinions about the merits of one flavor over another? Only the second verse contains an I-statement, and that’s a clue to the matter: “I feel your taste all the time we’re apart”. There’s much to unpack here, including the one use of first person. Harrison has shifted from criticizing a generic other inspired by Clapton to addressing his subject in a way that could be construed as either a love song or a devotional; he was prone to sliding back and forth between the idea of his wife and his god. So this introduces an element of the spiritual and a longing for the divine, in contrast to the earthbound, gluttonous delights in the chocolate box.

The line also contains an element of synesthesia, to “feel” a “taste”. Could one reasonably feel the taste of the chocolates, besides the tastes of the lover or the divinity? I think most people do indeed have taste-specific sense memories, of their grandmother’s chicken soup, or their dad’s marinara sauce, and yes, even a favorite candy associated with some holiday or other. Harrison was a staunch practitioner of meditation, which surely included some mindfulness toward his food. In the exercise of eating a piece of chocolate, you can think about many things: the origins of the cocoa, the places that grow sugarcane, what it smells like when it’s all cooking, the people and machines that made the candy, the flavor and texture of the candy itself, the words and colors in the design of the packaging, the aftertaste. There’s a lot of work that can be done in one bite, and this is a large part of why Harrison need not reach for another piece of candy to feel satisfied.

Then there’s the matter of “all the time we’re apart”. A favorite holiday candy is a reason to look forward to that holiday. We need not delve into pumpkin spice’s vast network of philosophical underpinnings; to simply invoke the two words “pumpkin spice” is somehow enough. So food is also associative, whether it’s attached to your grandmother or to Thanksgiving, or whatever else. In the time and space that get between us and our food, there’s a sense of longing. In verse three, he cautions, “You might not know it now / When the pain cuts through / You’re going to know and how”. Harrison obviously recommends some effort at detachment from this longing, as it’s the longing that transforms into our desire to consume even more of the candy once we have bridged time and space to get to it.

More explicitly, “What is sweet now turns to sour” in the second to last stanza, and finally, his exhortation: “We all know Ob-la-di-bla-da / But can you show me where you are?” The first half is a direct and pointed dismissal of the Beatles’ song “Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da”, which was one of Paul McCartney’s contributions to the White Album. Lennon and Harrison both despised the song, and “Savoy Truffle” was written during the same 1968 recording sessions when the clash was quite fresh and ongoing. Harrison appears to have deliberately, flippantly skewed the title of the song in his reference, and then there’s that “but” of objection right after it. McCartney and Harrison were in a very different place from one another by then, and within two years’ time, the Beatles would be over.

They had all just come back from studying Transcendental Meditation in India, and Harrison felt that McCartney’s ability to channel these new influences into their work was extremely weak. Comparatively, Harrison had spent the last two years or so working on the sitar with Ravi Shankar and had only just returned to the guitar as his main instrument. Yet the pop nonsense of “Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da” went to number one on the charts in several countries, while the comparatively complex composition of “Savoy Truffle” was buried in all its E-minor glory on side four of the double album and never charted at all, though many critics praised it. When we think of Harrison’s contributions to the White Album today, “Savoy Truffle” remains in the long shadow of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”.

One thing has always bothered me about “Savoy Truffle”, and that’s the title itself. What’s so special about the Savoy truffle, compared to the rest of what’s in the box? Why save that one for the title? Mackintosh’s candy box was titled “Good News”. To likewise title the song as such would have been very much in keeping with Harrison’s sense of irony, as the lyrics warn of the consequences of tooth decay and scary dentist visits. He did work “good news” into the verses almost like a pun, which is mildly clever, but Harrison usually offered song titles that were like subject headings, straight punches to his themes, and the obliqueness of “Savoy Truffle” at first glance doesn’t sit well in that category. As I sought in vain for a box of the long ago discontinued Good News, and then for any oldsters amongst my British friends who might recall the taste of its ingredients, it finally occurred to me that I was in some ways indulging in precisely the obsession Harrison was cautioning against.

I learned a lot about the house of Savoy, founded in the 11th Century and becoming the oldest reigning monarchy in Europe by the 18th century. I looked at a lot of pictures of the Alps and the southeast of France. I acquired numerous recipes for coconut fudge or something like a homemade Almond Joy, and shopped around looking for the right kind of brandy. All this, in search of one moment of concrete, authentic connection with the Savoy truffle itself that might have satiated me. But as Harrison knew, all that’s down in the rabbit hole is more rabbit hole. So I have not tasted the Savoy truffle, but I have felt its taste in Harrison’s song. During the holidays, I’ll try to bear this in mind.

Megan Volpert is the author of seven books on communication and popular culture, including two Lambda Literary Award finalists. Her most recent work is 1976 (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2016). She has been teaching high school English in Atlanta for a decade and was 2014 Teacher of the Year. She edited the American Library Association-honored anthology This Assignment Is so Gay: LGBTIQ Poets on the Art of Teaching.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario