THE PAUL MCCARTNEY WORLD TOUR (1989-90)

www.theatlantic.com

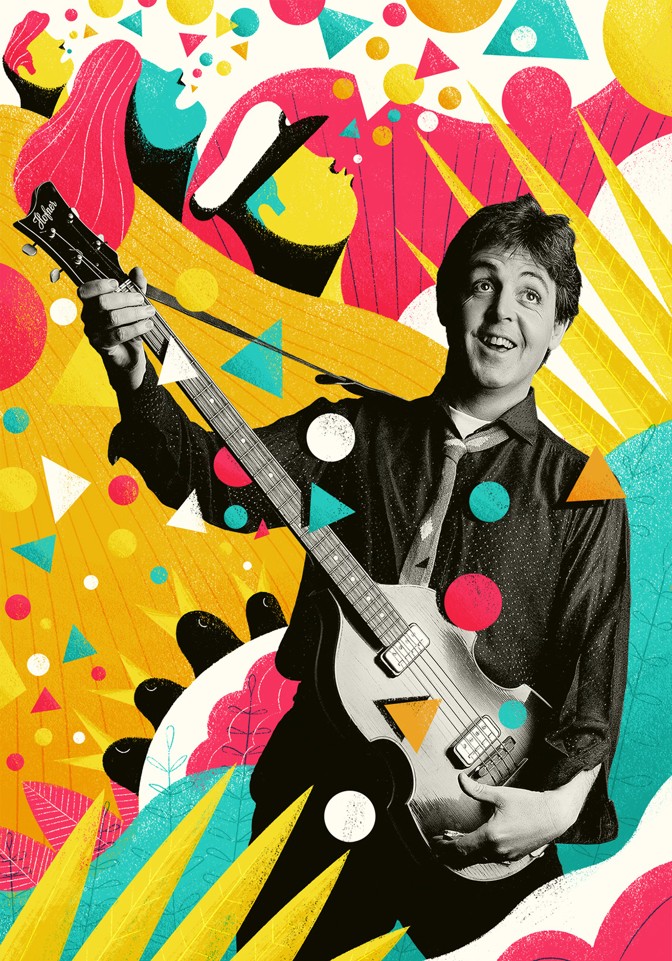

Paul McCartney Can’t Stop Making People Happy

Now 76, with a new album, the pop legend continues to delight and comfort the world with his music.

JAMES PARKER

THE ATLANTIC

NOVEMBER 2018 ISSUE

CATHAL DUANE

Does everyone already know the story of Paul McCartney and the milkman? I think I only just heard it, although at the same time it feels like a story I was told long ago, magical-indelible, back in the wavy chambers of my childhood. It goes like this: Paul McCartney, vital young Beatle, is lying in bed one morning in 1963 when he hears the milkman making his rounds. The milk bottles are clinking and clanking, doorstep to doorstep, and the milkman is whistling, as milkmen will. And what he’s whistling is the Beatles’ new single, “From Me to You.” Da da da, da da dum dum da. The pop star sinks back into his pillow, into his morning-warm mattress, vibrating head to toe with a nice horizontal buzz of gratification. He knows he’s cracked the code.

Very McCartney, that story—trite, profound, and instantly folkloric. The sound of a milkman’s whistle is proverbially mindless, the mere absent tootling of a city yawning awake. Yet how meaningful it is: McCartney’s song, sent out into the world, is being returned to him, pearl-like, on a ripple of the working-class unconscious. In Penny Lane there is a milkman whistling Beatles songs …

Sir Paul McCartney is 76 years old, and currently on a world tour to promote his new album, Egypt Station. “He can’t stop working or he’ll die,” I was recently assured over email by a friend who is the most passionate McCartney fan I know. “Also he plays the piano like a percussion instrument.” There he is, an automaton of his own vast gifts, thumping away at the keys. The first song on Egypt Station is “I Don’t Know”: lovely, trudging, Beatle-doleful piano, and McCartney singing in a voice striated with age. I got crows at my window / Dogs at my door / I don’t think I can take any more. The song is a dialogue between this figure—this small, embattled Paul, besieged by omens—and the supernaturally consoling presence that appears before him in the chorus. It’s all right, sleep tight / I will take the strain / You’re fine / Love of mine / You will feel no pain. This is a presence that we recognize from “Let It Be,” although the suggestion of anesthesia is new. Is it Mother Mary, or is it Morpheus, easeful death?

© Getty

McCartney may have made more people happy—gapingly, tinglingly, mind-cancelingly happy—than any other artist, alive or dead. W. H. Auden wrote, In headaches and in worry / Vaguely life leaks away. Paul McCartney has been the opposite of that. The rush of early Beatles; the towering artistic magnanimity of middle-period Beatles; the epic fragmentations of late Beatles; and his solo songbook, which sometimes feels like a wild succession of one-hit wonders, of brilliant, bulbous, unrelated novelties—in every phase, in every style, he has insisted that we not allow our lives to leak away. His scope is immense. Think for a second about Revolver, and try to hold in your head the idea that the Larkin-esque elegist who wrote “Eleanor Rigby”—that rhapsody of glumness, that death-of-God song—is also the man playing bass on “And Your Bird Can Sing,” with a technique as restless and fiery-fingered as The Who’s John Entwistle’s but with an extra dimension of melodic bounteousness and buoyancy, of pure, generative tune-energy. (I just listened to it again, and burst out laughing.)

“Penny Lane” is the perfect summation, in a way: a trippily colorized vision of everyday life as a harmonic whole, a sublime congruity or comedy, a humming, sanctified circuit in which the brass-band trumpeter sounds like Bach and the fireman keeps a portrait of the Queen in his pocket. If you watched McCartney recently on James Corden’s “Carpool Karaoke,” doing a nostalgia tour of Liverpool with his host blushing and chirping at the wheel, you’ll have seen how people—young, old, of every shape and color—respond to him. He travels in a pocket universe of delight. You’ll also have seen him carefully adding his signature to the scuffed, graffitied street sign of the real Penny Lane: signing it like an artist signs his creation.

“Poetry reveals language’s underlying metrical and intonational regularity, and its tendency to pattern its sounds,” the Scottish poet and musician Don Paterson writes in his new book, The Poem. Poetry does that, and so does Paul McCartney. He can’t help himself. Swaying daisies sing a lazy song beneath the sun. That’s from 1968’s “Mother Nature’s Son,” perhaps the single most pristine utterance of McCartney’s muse in his whole corpus. The softly dulled guitar-chime, the foot-tap and the lulling rhyme, the sleepy delivery: Find me in my field of grass / Mother Nature’s son. This is not 20th-century music. It has nothing to do with sex, politics, the trapped self, or the long chore of consciousness. This is pre-modern, pre-adult, pre-gravity. It runs straight back to the first climates of the imagination, to the place where William Blake wrote his Songs of Innocence: Piping down the valleys wild / Piping songs of pleasant glee / On a cloud I saw a child.

And then, from the same era and acoustic realm, there’s “Blackbird,” shimmering in the predawn: Take these broken wings and learn to fly. For me this is McCartney self-soothing in the face of the Beatles’ meltdown, the impending bummer of individuation. It was from the White Album sessions, after all—everybody writing his own songs, grumpy, with Yoko Ono sitting harbingerlike in the studio, a carved, impassive face in a cavern of hair. So what’s a sad but incorrigibly optimistic bandleader to do, if not direct himself right into the dark, into the lustrousness, into the deep blackbird-feather gleam of promise? Blackbird, fly / Blackbird, fly / Into the light of the dark black night. (Limpid squirtings of actual blackbird-song conclude the track, the bird as compulsive a melodist as McCartney himself.)

© Getty

Biography supplies the platitudes: how the loss of his mother when he was 14, and the subsequent need to make the best of things, produced the hard shell of perkiness. Post-Beatles, freed or cut off from the drug-drag and the sourly twanging intellect of John Lennon, what happened to his talent? By one account, it accelerated into nonsense: form without content, songs about nothing but the fact that they were songs. But that’s not quite right. I was 9 when “Mull of Kintyre” came out, in 1977, and though I’m not from Scotland, I recognized it immediately as my birthright, a song of my blood, the only possible way to sing about this hitherto uncelebrated peninsula, Kintyre. Oh, the bagpipes. Oh, the drums! (In the U.S., interestingly, this song did nothing. In the U.K., at the top of the charts, it dueled titanically with two of the mightiest singles ever released: Queen’s “We Are the Champions” and Abba’s “The Name of the Game.”)

And what about the thundering emotional nudism of “Maybe I’m Amazed,” the least macho love song ever? Maybe I’m amazed at the way you love me all the time / Maybe I’m afraid of the way I love you. To be amazed and afraid—a biblical echo can be heard in there, from somewhere deep in McCartney’s Liverpool-Catholic wiring. Mark 10:32: “And Jesus went before them: and they were amazed; and as they followed, they were afraid.”

“Love you, Paul,” says a shaven-headed man on “Carpool Karaoke,” outside the pre-Beatles McCartney-family home on Forthlin Road. He says it with easy Liverpudlian warmth, but also with a degree of urgency. Because it’s important that McCartney knows this. Let us not be afraid of the way we love him. For more than 50 years he’s been making us happy, giving us comfort, a genius who scoops tunes out of the air with his hands. It’s the milkman’s whistle, it’s the music of the spheres. From him to us, and back again. Da da da, da da dum dum da.

This article appears in the November 2018 print edition with the headline “The Eternal Sunshine of Paul McCartney.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario