The Beatles' 'Sgt. Pepper's' Turns 50: Is It The Best Album Ever?

by William Goodman

5/26/2017

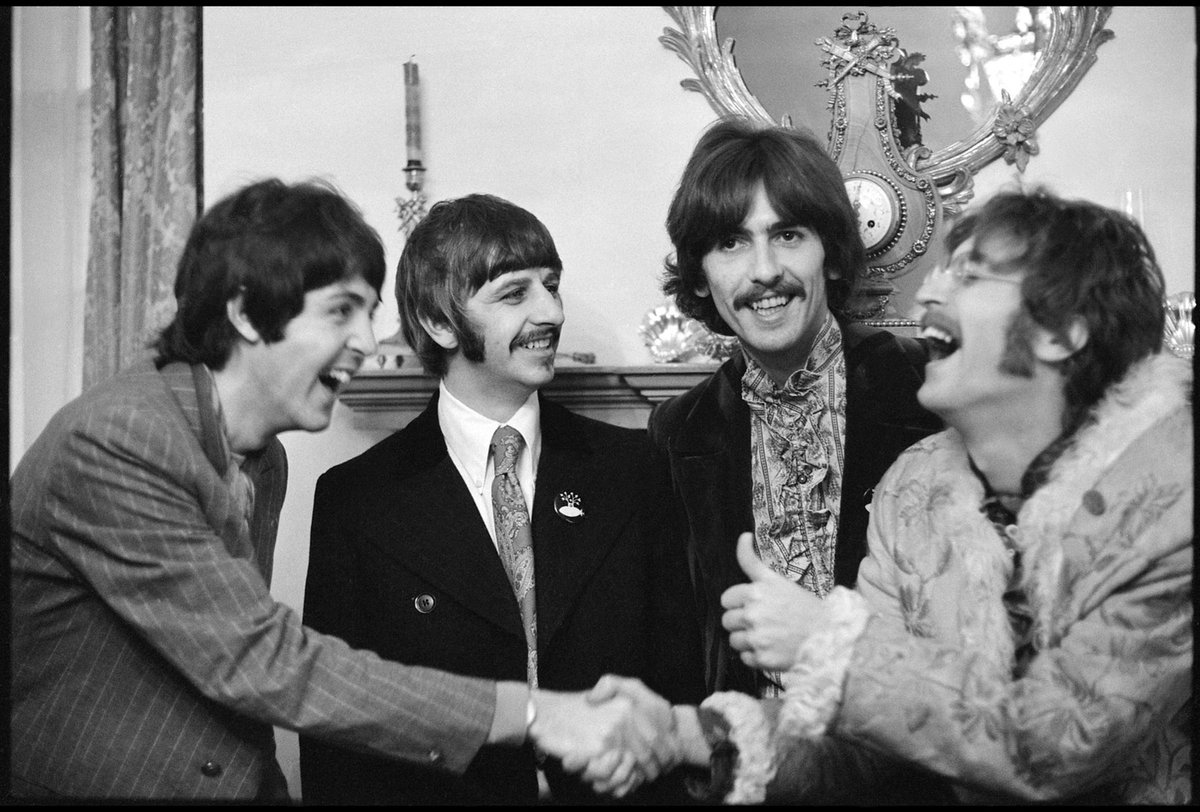

The Beatles during a photocall for 'Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.'

Mark and Colleen Hayward/Getty Images

The Best Album of All Time. That’s one hell of a claim.

Even if The Beatles’ eighth studio album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band -- released 50 years ago, May 26, 1967, in the U.K. -- is the musically ground-breaking, hyper influential career high-water mark from The Best Band of All Time, those can still sound like fighting words. But there’s no hyperbole here. There’s widespread consensus: Sgt. Pepper’s has topped its fair share of Greatest Albums of All Time lists from music magazines and websites, on both sides of the Atlantic, pleasing all the stripes of listeners, from old curmudgeon critics to shrieking teenagers. Sgt. Pepper’s is indeed that album, and half a century on, the argument for that grand statement -- one made since the very week of its release -- has only grown stronger.

And all this was either pre-ordained or a glorious coincidence, because Sgt. Pepper’s became a crossroads for the band -- and the world.

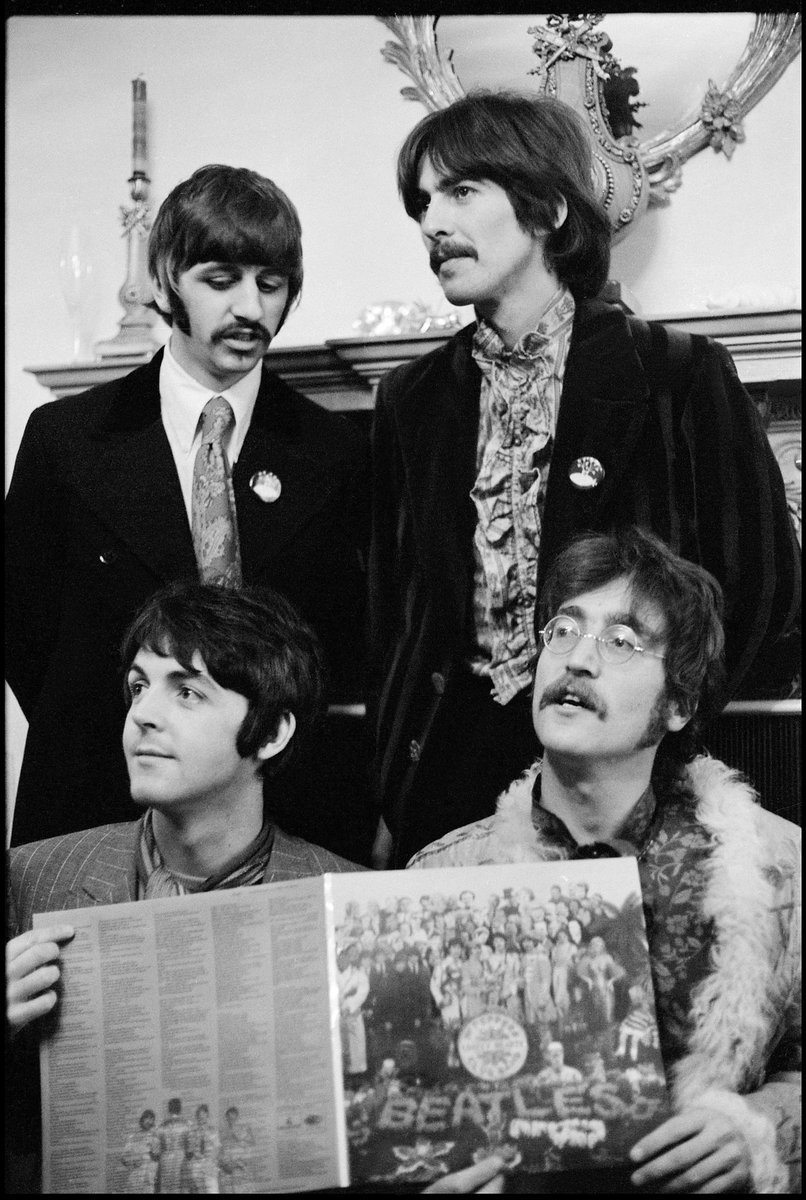

The Beatles, 'Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band'

Courtesy Photo

The Beatles, 'Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band'

A series of events that nearly broke up The Beatles instead led a group of musical geniuses to produce their most genius work. By 1966, The Fab Four -- the Beatlemania Beatles, the four mop-topped Liverpool lads in suits and shiny black leather boots -- were on death’s door. Over their past few releases, Rubber Soul and Revolver, the band spent more and more time in the studio with production guru/Fifth Beatle George Martin, as their grand (and increasingly intoxicated) musical visions becoming more reliant on his expertise -- and drifted further from their old pop sound. They embarked on a beleaguered world tour, with the band pursued by death threats and political mayhem in Asia, followed by Lennon’s infamous, Bible Belt-insulting “more popular than Jesus” remark in the U.S. With stadiums half full (and lacking the shrieking teenage girls of yore) the band became dissatisfied with the quality of their performances, not attempting even one track from the ambitious Revolver. The gap between the Old Beatles and New Beatles was widening and threatening their very existence. So they decided to quit the road. We thank you for this decision.

After a nearly three-month break, the band reformed with new ideas. In the downtime, George Harrison had visited India, immersing himself self-discovery and learning the sitar. John Lennon had joined the visual art and film world (meeting Yoko Ono), and Paul McCartney returned from an African vacation with a few screwball ideas: What if the Beatles returned to their roots, penning songs about their childhood home of Liverpool? This resulted in "Strawberry Fields Forever" and "Penny Lane" (which EMI rushed released to dispel breakup rumors.) The band also dove into another of McCartney’s ideas: What if The Beatles, in an act of total defiance of their former identities, adopted the persona of an old military marching band, complete with colorful officers’ uniforms?

In November ’66, the Beatles hit Abbey Road Studios with more freedom than ever. While “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” didn’t make the album, much to Martin’s dismay, the lush, experimental pair of tracks set the tone for the new sessions. With Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick, the band pushed the very limits of recording technology. Having retired from the road for good and knowing the songs wouldn’t be performed live, they saw the studio as an instrument, using tape effects, double-tracking, pitch control, sound suppression, signal processing and other sound technologies. Another system used tape recorders to double a sound. On a joke, Lennon called it a “Flange,” inadvertently inventing the term for a now popular tone setting on essentially every modern guitar amplifier.

And there were instruments galore: Harpsichords, tamboura, Mellotron, harmonium, woodwinds, and a variety of guitars, pianos, and tambourines. And, of course, a 40-piece orchestra. The power of the studio-centric approach is heard across the LP, especially on “With a Little Help From My Friends,” “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” and the epic “A Day in the Life.”

The band was tighter and more productive than ever, and Sgt. Pepper’s marked a new dynamic in the McCartney-Lennon songwriting partnership. The myth of Sgt. Pepper’s is that McCartney was becoming the dominant creative force, surpassing Lennon, the most senior member, founder, and longtime de facto leader. Yes, Macca penned more than half the LP’s 13 tracks and the grand concept is uniquely his, but Lennon is the emotional core. Without Lennon, McCartney’s concept would’ve sounded bloated and saccharine. Without Macca, Lennon’s songs could never reach their musical grandeur. Lennon delivered the base feeling. McCartney, with Martin and Emerick’s studio skills, dressed by them up like a Savile Row tailor.

The band spent 700 hours crafting Sgt. Pepper’s and it paid off. It’s the first true concept album and while the actual concept was restrained to the iconic cover art and a few tracks, including its namesake opener and reprised closer, its sounds far surpassed any framework: there’s the shuffling big band camaraderie of Ringo Starr’s “With a Little Help From My Friends”; Lennon’s brass blasting “Good Morning, Good Morning” and trippy Ringling Bros-style circus “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!”; McCartney’s bassoon-led “When I’m Sixty-Four,” spaced-out show tune “Lovely Rita” and avant-garde classical “She’s Leaving Home.” Starr’s drumming is tasteful throughout, never overdone, and Harrison shines on a spiritual solo sitar jam “Within You Without You,” and adds guitar flare and texture.

The best songs are, arguable, total collaborations between Lennon and McCartney, with the former bringing the basic song and the latter lifting it to glorious heights. “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” thought to be a LSD tribute but actually an ode to a drawing by Lennon’s son, has an iconic organ opening and explosive sing-along chorus. Then, of course, there’s “A Day in the Life,” a monument to groundbreaking recording and studio technologies. It’s Lennon’s cut-and-paste tale of newspaper headlines, building to a moment of psychedelic piano and horn dream with McCartney waking up and rolling out of bed to the sound of an alarm clock. It continues to blow listeners’ minds, and popularized Lennon’s “I’d love to turn you on” catchphrase, resonating with the overall cultural movement.

The LP was an immediate hit and cultural flashpoint. It spent 27 weeks at the top of the U.K. albums chart and 15 consecutive weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 in the U.S., and was praised for its genius innovations in recording techniques and kaleidoscopic sound that united pop music with other sounds and genres. It became one of the best-selling albums of the year, then the decade, and now—with more than 32 million copies moved worldwide—one of the best-selling in history. It won four Grammys in 1968, becoming the first rock album to win Album of the Year (it did, after all, codify the idea of an album as a cohesive work of art). Sgt. Pepper’s was the soundtrack to the Summer of Love, spreading the Beatles’ vibes for the bubbling alternative culture across the globe.

Its cultural impact was just immense: As Abbie Hoffman, the political and counter-culture icon, said in a 1987 documentary on the album: “There are two events, outside of my inner family circle, that I remember in life. One is JFK’s assassination. The other was where I was when I first head Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.”

The album was the vanguard of the so-called hippie movement. “There was so much attention given to not just the Beatles, but all the changes that were happening in fashion, film, poets, painters, the whole thing. It was a mini renaissance,” Harrison said in the same doc. “There were a lot of people trying to go on the same trip together regardless of what they were doing.

“There was a bond formed between a lot of people,” he added. And Sgt. Pepper’s was the primary cultural adhesive. Fifty years on, that hasn’t changed much -- and isn’t that a damn good definition of “Best”?

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario