The Fireman: Youth (at left) and Paul McCartney

www.theguardian.com

‘I treated working with Paul McCartney as art’ – Youth on his five favourite albums

The producer and Killing Joke bassist has produced everyone from Alien Sex Fiend to Bananarama. Here he picks the best albums he has worked on, from Pink Floyd to the Orb

As told to Joe Muggs

Thursday 18 February 2016

‘Punk wasn’t ever about dumbing down’ … Martin Glover AKA Youth, 1980. Photograph: Tim Roney/Getty Images

The Fireman

Rushes (1998)

I treated working with Paul McCartney as art and talked about artistic process. Someone of that stature could do anything, work with anyone, any day – which is potentially a little paralysing. He also wanted to escape his legacy a bit, so the psychology for me as a producer was to get him engaged and inspired about the details of the process. So we’d discuss, say, William Burroughs and his cut-up technique, or Willem de Kooning (who he had known because Linda’s dad was his agent) and his methods, and go from there.

I’d also heard that he liked promptness, so I’d get in the studio really early each morning, and when he came in I’d already have a few ideas running and ready to work with. The album I’m proudest of is Rushes, The Fireman’s second. We’d do a lot of field recording, playing instruments outdoors, sampling natural sounds, even Linda’s horses. I didn’t know at the time that she was dying and we completed it soon after her death, so it’s a real memorial piece to her: she sings and speaks in some parts of it, too, and is very present throughout. It was a heartbreaking experience, but a huge privilege for me in my small way to be part of their journey.

Paul and Linda McCartney, 1997. Photograph: Steve Wood/REX/Shutterstock

Pink Floyd

The Endless River (2014)

When I was 14, before I even knew what getting high was, Wish You Were Here showed me how a record could open a door into a world. It gave me the criteria of what music production could be. So of course, as a producer, I really wanted to get behind the scenes and understand what made that chemistry work. When David Gilmour invited me to his farmhouse, I thought I would be working on his solo album, but as he played me all these outtake tapes from The Division Bell sessions, I gradually twigged, with some delight and trepidation: “Is this going to be a Floyd album?” He asked me to take this material away and “make it sound good” – which is always a nice brief – “and make it sound more like us.” Then he and Nick Mason overdubbed new parts on top. Gilmour’s brilliance is letting the process unfold very naturally, and then going back with a microscopic eye and finessing every detail. It was strange because the Division Bell material had a certain Orb influence in it, and there was older material like Rick Wright playing the Albert Hall organ, too, so we were folding several decades together into something timeless. It’s an album I can still listen to, and it will still take me away somewhere very special.

The Orb

Adventures Beyond the Ultraworld (1991)

The Orb essentially emerged from Alex Paterson’s record collection, morphed through a mixing desk, with beats added. This came out of many, many long sessions DJing in the backroom of Paul Oakenfold’s Land Of Oz club and at the KLF’s Trancentral studios. One thing I’d learned – funnily enough from Pete Waterman, who produced mine and Jimmy Cauty’s [of the KLF] album as Brilliant – was that you should never hide your influences. Quote them directly and, ironically, you end up more original. So when sampling came in, this is exactly what we did. Little Fluffy Clouds was written in my bedroom with a little sampler, and was the linchpin: that, and the backing that Alex made for Primal Scream’s Higher Than The Sun were where it went beyond essentially jamming into something rather more structured, and Adventures Beyond the Ultraworld kind of formed around that. Alex had different ideas going with different people for each track, a few mini-teams working simultaneously, then we brought them into bigger studios and essentially DJed them all together in the final mixing process to create a complete whole. There were no rules for what we were doing, but through a series of fantastic accidents and experiments I think we captured something very special about that time.

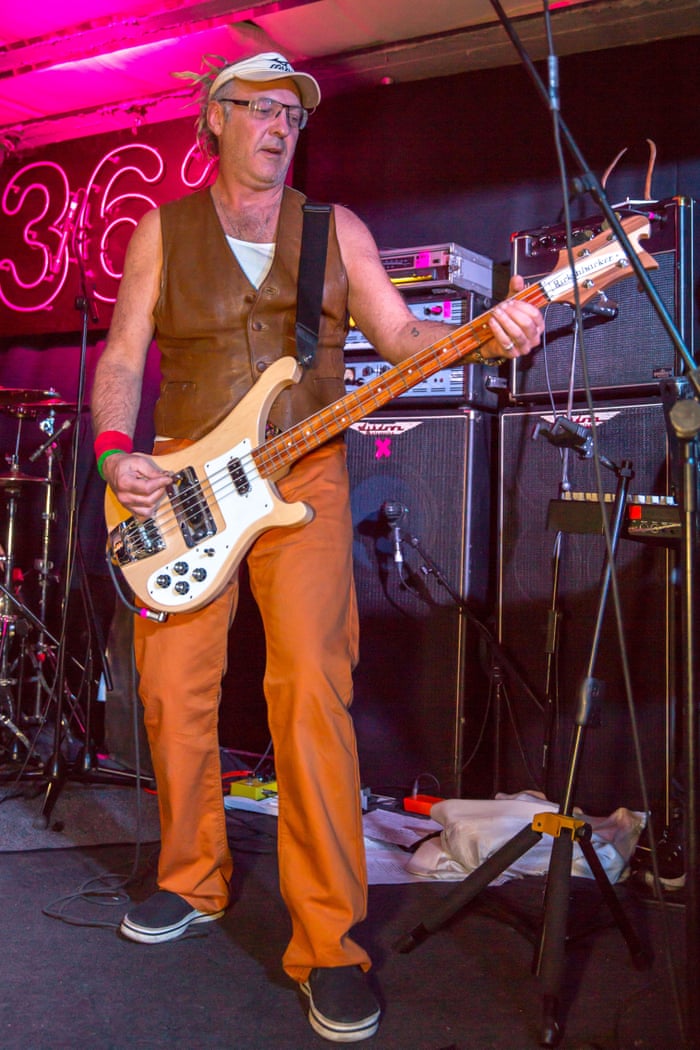

Youth performing with Killing Joke, 2015. Photograph: Startraks Photo/REX/Shutterstock

The Verve

Urban Hymns (1997)

There’s something very wonderful about being part of a band’s adventure as they break through. I don’t know what happened to Richard Ashcroft just before Urban Hymns: the band had been this very jamming, psychedelic act on the gigging circuit for two albums – then the songs seemed to just come to him from above, absolutely perfectly formed, with the knowledge of how to sing them. Recording his vocal was probably the easiest I’ve ever done, but the challenge then was to make the music and production reach the same level, and that took over six months. As ever with a band, there’s a lot of conflict resolution for the producer, a lot of: “Well let’s try recording both versions and see which one sounds best.” A lot of stunning material was recorded that never came out and I’m hoping that on the 20th anniversary, maybe some of it can be heard on a special edition. It was worth all of that effort though, and it ended up one of the best-sounding records I’ve ever done - due mainly to Chris Potter who engineered and mixed it. He aced that one.

Killing Joke

Pandemonium (1994)

I suppose it seemed a bit of a risky decision, not just to rejoin the band I’d left a decade before, but to sign them to my label Butterfly and produce them, too. It certainly didn’t go smoothly – we’re all alpha-male types who want our own way, and one discussion ended with Jaz Coleman [singer] hurling a whisky bottle at my head – but it was an extraordinary process. We may have been punks when Killing Joke began, but punk wasn’t ever about dumbing down: I never hid my love of disco and Pink Floyd, and we brought all of that, plus dub reggae, Can and Kraftwerk into what we did. When it came to Pandemonium, I’d had the intervening time to explore production more, and we wanted all those sounds and more. There was classic rock and industrial, too, and we had the confidence to record Egyptian string sections, to even record vocals in the King’s Chamber of the Great Pyramid, to have a brave, adventurous time. And I think all that drama, conflict and history that we had were just channeled right: it became our biggest-selling album and we still close shows with the title track.

• This month the Music Producers Guild

awarded Youth the PPL Outstanding Contribution to UK Music.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario