www.acousticguitar.com

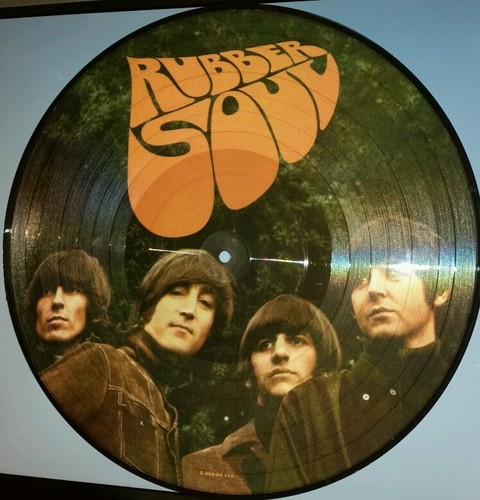

The Beatles' 'Rubber Soul' Turns 50!

Acoustic Guitar

Posted on December 3, 2015

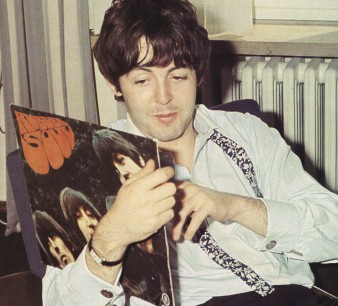

It was 50 years ago today (December 3) that the Beatles’ Rubber Soul, a near-consensus choice as one of the best albums ever made, was released in the UK. This was the album that truly signaled the group’s intention to move beyond the sound that had inspired the first wave of Beatlemania. The songs, the harmonies, and George Martin’s production touches were more stylistically varied and sophisticated than on the group’s earlier records—though the string quartet accompanying Paul McCartney’s Epiphone Texan acoustic guitar on the already-released “Yesterday” pointed in new directions.

The same day “Yesterday” was recorded at Abbey Road Studios in London—June 14, 1965—the group also cut McCartney’s jaunty, countrified “I’ve Just Seen a Face,” another song propelled by acoustic guitar: McCartney's Epiphone and John Lennon's and George Harrison's Gibson J-160E's. That track appeared on the UK version of Help! (released in August ’65), but ended up as the lead-off track of the American version of Rubber Soul, released three days after its British counterpart. This was standard operating procedure with Beatle albums, where the American albums always differed from the British ones—in the case of Rubber Soul, the shorter American version did not contain the songs “Drive My Car,” “Nowhere Man,” “What Goes On” and “If I Needed Someone,” and added “I’ve Just seen a Face” and “It’s Only Love.” All four of the excised songs showed up on a June 1966 American album release called Yesterday and Today, along with “Yesterday” and three songs plucked from the British Revolver album, which was released in August 1966 (and missing those songs on the American Revolver). This absurd practice of releasing different albums in the U.S. and the rest of the world ended with Revolver.

When the UK Rubber Soul was released on CD for the first time in 1987, it effectively made the bastardized U.S. version obsolete, and subsequent generations of digital music consumers now mostly know only the British albums, which are, of course, the ones the Beatles approved originally. But for literally millions of Americans of a certain age (you know who you are), the Rubber Soul of memory still starts with that acoustic one-two punch of “I’ve Just Seen a Face” followed by “Norwegian Wood,” featuring Lennon on J-160E and George Harrison on Lennnon’s Framus Hootenany 12-string (which had been previously heard on “Help!” and “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away”).

Several other tracks on both versions of Rubber Soul feature prominent acoustic guitars, as well: “Michelle” has a fingerpicked acoustic line played by McCartney that he says was directly inspired by Chet Atkins, as well as strumming from Lennon, and Harrison on 12-string; “Girl” also has the two 6-string acoustics and the 12-string; Lennon plays the rhythm guitar line on “I’m Looking Through You” on his Gibson; and the album-closing “Run for Your Life” also has Lennon on acoustic.

Even though the Beatles made their final tour in the summer of 1966, they played only two songs from Rubber Soul/Yesterday and Today during their short sets, “Nowhere Man” and “If I Needed Someone,” and there were no acoustic guitars in sight. Alas, there don’t seem to be any video versions of the Beatles performing any of the acoustic-guitar oriented tracks on Rubber Soul. So this week’s Throwback Thursday flashback features just one Beatle: Here’s Paul McCartney and his mates (wife Linda, Hamish Stuart, “Wix” Wickens, Robbie McIntosh, and Blair Cunningham) playing “I’ve Just Seen a Face” on a 1991 airing of MTV Unplugged.

businesslessonsfromrock.com

An album that left a footprint

Business Lessons from Rock

December 2, 2015

Fifty years ago this week one of the most important records in rock history was winging its way to music stores across North America.

Rubber Soul was a major pivot by The Beatles—a distinct turn towards more sophisticated songwriting and eclectic instrumentation. (The album was considered by some to be their first “work of art.”) It was their answer to a string of signature hits—all blockbusters—by their competitors in the previous months: “Tambourine Man” by The Byrds; “Satisfaction” by The Rolling Stones; and “Like a Rolling Stone” by Bob Dylan.

The day after RS was released, the Byrds’ second monster hit, “Turn Turn Turn,” became the #1 single, soon to be followed by “The Sound of Silence,” sung by an unknown folk duo named Simon & Garfunkel. Rock had come of age! (It’s true that The Beatles had recently scored a #1 hit themselves—with “Yesterday”—but it was time for them to assert their mastery of the album format.)

Rubber Soul soon became #1 (displacing The Sound of Music as the top-selling album) and remained on the US charts for most of 1966. A work that greatly expanded the bounds of pop music at the time—featuring inventive lyrics, exotic sounds, and creative production techniques—Rubber Soul remains one of the most critically acclaimed rock albums and is ranked #5 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time.” Tracks such as “In My Life,” “Norwegian Wood,” and “Michelle” still stand the test of time.

But to those in business—who live in a world of projects, deliverables, and deadlines—Rubber Soul should represent another kind of achievement, as mentioned here. No other business author or music writer has picked up on this, so I’ll continue to trumpet it: RS was one of the most amazing time-to-market breakthroughs in the history of the music business—if not business at large—especially considering the quality and originality of the product.

At the beginning of October The Beatles had less than two weeks to write (mostly from scratch) an album’s worth of songs (14 new compositions) plus two more for their next single. Recording sessions had to begin by October 12th so that by November the tracks could be mixed, mastered, pressed, packaged, and distributed for the early December release date, in time for the Christmas rush.

They delivered on time, despite running late at key stages of the project. The recording spilled into November and they still needed more songs. Discarded compositions were revived, such as “What Goes On” and “Wait.” New songs were whipped up almost on the spot, such as Lennon’s “Girl” and “The Word” and McCartney’s “You Won’t See Me” (which was brilliantly arranged—and nailed in two takes!). Sessions routinely ran until 3:00 am or later. But by November 15th they had finished recording and mixing the tracks, just in time for the manufacturing cycle to kick in to get the album into the stores in the UK on Dec 3rd and in North America on Dec 6th—as scheduled. And their soon-to-be smash hit single “Day Tripper”/”We Can Work It Out” was also released the same day!

So how was it that the Beatles could deliver such a breakthrough product in breakthrough time?

Well, when it comes to the Beatles I’ve usually focused on two differentiators, as I’ve done previously:

1. The Beatles were results-obsessed. This was a small business team with a long track record of performance. John, Paul, and George had already been together for eight years so they knew a few things about collaboration under pressure. In Hamburg clubs in late 1960 the band was required to perform 4 to 6 high-octane sets a night, often seven days a week. Once manager Brian Epstein took over a year later they had to play over 30 gigs a month. In the two years running up to their first recording session they played over 700 performances. And they loved impossible deadlines.

In 1963 The Beatles recorded a world-class rock & roll debut album in one 13-hour session (recording instrumentals and vocals the same day), an impressive feat at the time. Much more was expected of a Beatles’ album by 1965 and the competition—including the Beach Boys, Stones, Byrds, and Kinks—had significantly raised the bar. To achieve maximum quality, albums were rarely recorded “live” anymore—that is, with band members singing and playing at the same time. In the studio artists laid down the instrumental “basic tracks” first (e.g., guitar, bass, drums), then vocal tracks (lead and background), then instrumental overdubs (guitar leads, keyboard additions, hand claps, whatever). In the world of multi-track recording, producing 16 cuts of top notch material in a few weeks was a lot to ask, but the lads responded.

2. The Beatles embodied breakthrough innovation—before the term existed. As I’ve said many times, their off-the-charts creativity kept them on the charts. They were determined to stand out from the pack in everything they did. They broke the mold in song craftsmanship, vocal arrangements, musical accompaniment, engineering and production, and more—eventually revolutionizing album artwork and packaging as well. They even set fashion trends and advanced a consciousness movement (based on meditation and medication). As Newsweek reported, “What the Beatles did in the '60s remains the most thrilling surge of creativity in the history of pop culture.”

That the Fabs intended to be the most innovative force in rock & roll may be a contentious claim, but it’s one I’ve repeatedly made, especially when arguing with Ken Melville, my late pal (whom I miss big-time), as captured here in a 2012 post and commentary thread. They certainly wanted to be different—and they succeeded.

And with Rubber Soul, we might say, they left a huge footprint.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario