www.jewishpress.com

The Beatles In Israel: The Concert That Never Was

By: Saul Jay Singer

The Jewish Press

Posted on: June 24th, 2015

The Beatles are still enormously popular in Israel, much as they are across the world, but only Israel has a John Lennon Peace Forest. (The Jewish National Fund sought, and received, permission from Yoko Ono, Lennon’s widow, for the Peace Forest project, which began with the planting of trees by Jewish and Arab children on a plot of land outside Tzfat on Tu B’Shevat 2006.)

Yet by no means was this always so. While Beatlemania was sweeping the world in the mid-1960s, the Beatles were generally viewed in Israel as a corrupting influence, few of the their hits found their way onto Israeli radio, and Israelis’ exposure to the Fab Four was generally limited to reading about them in the newspapers.

Under such circumstances there was no logical reason for the Beatles to perform in Israel – but in 1964 one man, an Israeli promoter named Yacov Ori, had other ideas.

Ori knew the Beatles had a Jewish manager, Brian Epstein, the so-called Fifth Beatle who first discovered the group in 1961 and is credited for much of their success. As the eldest son of devout Jews, Epstein was the scion of the union of two wealthy Jewish families whose fortune was established by Lithuanian immigrant grandfather Isaac, who opened a furniture store in Liverpool in the early 1900s. Brian was bar-mitzvahed at the family’s synagogue in Greenbank Drive, Liverpool.

After an untimely death from an overdose of sleeping pills at age 32 – mere weeks after he paid a traditional shiva call in Liverpool upon his father’s death – Epstein himself received an Orthodox Jewish burial and a Hebrew grave stone.

In any case, Ori discovered that Epstein’s mother, Malka, had relatives living in Israel, and through them he persuaded Epstein to bring the Beatles to the Jewish state. Plans were made for Chipushiot Ha-Ketzav (“the Rhythm Beatles”) to play at Ramat Gan Stadium on Thursday, August 20, 1965.

(It’s interesting to note that, in an entertaining pun, many anti-Beatles Israelis referred to the band as Chipushiot Ha-Zevel or “the dung beetles.”)

Exhibited on this page is a very rare ticket to that concert, which never took place – and therein lies a tale.

* * * * *

Any number of false narratives regarding the reason the Beatles did not perform at Ramat Gan continue to circulate, ranging from a dispute between Ori and another music promoter, Giora Godik, to the recalcitrance of Golda Meir.

According to the latter account, the fault lies squarely on the shoulders of Golda, who, as minister of foreign affairs at the time of the Beatles debacle, considered the band to be a corruptive influence. There is, of course, no evidence that Golda even knew, or cared, that the Beatles existed, and the true story is very different – and much more interesting.

First, Ori was faced with what proved to be an insurmountable problem: Israel was short on foreign currency and the government maintained strict supervision on every dollar leaving the country. Ori simply could not secure the requisite foreign funds to pay the Beatles, who scoffed at the very idea of being paid in Israeli lira, so he pursued the only possible solution: he and Israeli promotor Avraham Bugtier joined to make an official application to the Finance Ministry, the Israeli government agency charged with determining which foreign artists should be given those precious and rare dollars. The ministry flatly denied the request.

Many of those who know the story feel the concert would not likely have been held even had the Israeli government approved the promoters’ access to foreign currency because the organizers – who did not fully grasp the true scope of the Beatles’ worldwide popularity and the demand for them – would have been unable to raise the funds necessary to pay the substantial fee demanded by Beatles management.

In January 1964, Ori and Bugtier appealed the Finance Ministry’s decision by submitting a petition to the Inter-Ministerial Committee for the Authorization of Bringing Foreign Artists to Israel, Israel’s official guardian of good taste and morality. Operating under the auspices of Israel’s Education Ministry, the committee was charged with bringing performers to Israel, evaluating their artistic level, and preventing problems during their performances.

(The committee was then headed by director general Yaakov Sarid, the father of Yossi Sarid, who went on to become a controversial leftist Knesset member and who also later served as Israel’s minister of education under Prime Minister Ehud Barak.)

The thirteen-member committee denied Ori’s appeal and adopted Resolution 691, to wit: “Resolved: Not to allow the request for fear that the performances by the Beatles are liable to have a negative influence on the [country’s] youth.”

Israel thereby replaced Beatlemania with Beatlephobia.

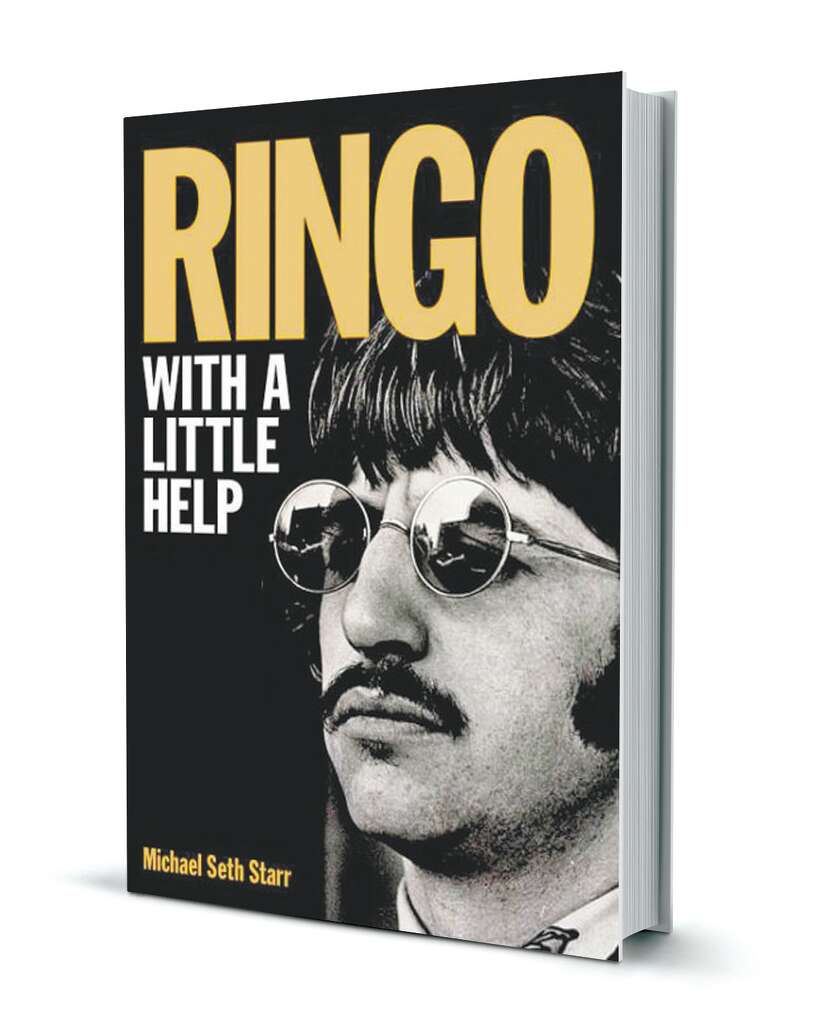

Israel banned John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr from playing to the nation

Israel banned John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr from playing to the nation

The two promoters filed yet another appeal, in response to which the committee launched a comprehensive investigation of the Beatles, including the solicitation of information from Israeli embassies around the world and from the foreign ministry’s cultural relations department. Israeli media blasted the group and insisted that the committee act to protect the nation’s youth; one newspaper even went so far as to complain that committee members had been listening to the “yeah-yeah-yeah howls which are capable of striking dead a real beetle.”

Ori again met with failure when the committee ultimately issued Resolution 709, ruling that the Beatles would be denied the requisite permits to perform in Israel because the band’s music was of no artistic value; because its appearances had led to mass hysteria where they performed; and because its influence would undermine the values of Israeli youth. It later added that even American officials dealing with young people had called for banning the group from performing due to rioting, mass hysteria, injury, and the need for police intervention.

The “mass hysteria” cited by the committee undoubtedly encompassed not only the general Beatlemania phenomenon then crossing the globe, but also the specific madness that had been generated when British pop singer Cliff Richard, who dominated the British rock scene pre-Beatles, played Israel in 1963. Many hundreds of fevered Richard fans went to Lod Airport to welcome him, shrieking, screaming, and trespassing onto the tarmac, and the police were barely able to maintain order. Fearing a repeat of this behavior for the Beatles, the committee cancelled their concert in the alleged interest of public safety.

But the matter was by no means final, as the debate in Israel over the Beatles grew, even reaching the hallowed halls of the High Court of Justice. In April 1965, the court ruled that the committee did, in fact, have the authority to bar foreign performers from performing in Israel and that it had not exceeded its authority in refusing to permit the Beatles to play in Israel.

In February 1966, the Beatles issue even “rocked” the Knesset when Minister Uri Avneri posed a parliamentary question to Deputy Education Minister Aharon Yadlin regarding the committee’s reasons for not allowing the Beatles to perform in Israel.

Avneri argued that the band members, who had also become favorites with members of the British establishment, had even received awards from Queen Elizabeth. In response, Yadlin reiterated the view of the Education Ministry that the band had “no artistic value” and that its appearances generated mass public hysteria causing damage and requiring police intervention.

Back in 1999 I was considering writing an article on the Beatles and Israel and, as such, sought to interview Ori. I found a listing in the Israeli phone book for an entertainment agent named Yakov Ori at 17 Strand Street in Tel Aviv. I called his office, only to learn that he had passed away in 1980.

* * * * *

Ultimately, the Israeli government came to recognize the error of its ways and, at a ceremony at The Beatles Museum in Liverpool in January 2008, Ron Proser, Israel’s ambassador to the United Kingdom, formally met with John Lennon’s sister, Julia Baird, and presented her with an official letter addressing John:

We would like to take this opportunity to rectify a historic missed opportunity which unfortunately took place in 1965 when you were invited to Israel. Unfortunately, the State of Israel cancelled your performance in the country due to lack of budget and because several politicians in the Knesset had believed at the time that your performance might corrupt the minds of the Israeli youth.

There is no doubt that it was a great missed opportunity to prevent people like you, who shaped the minds of the generation, to come to Israel and perform before the young generation in Israel who admired you and continues to admire you.

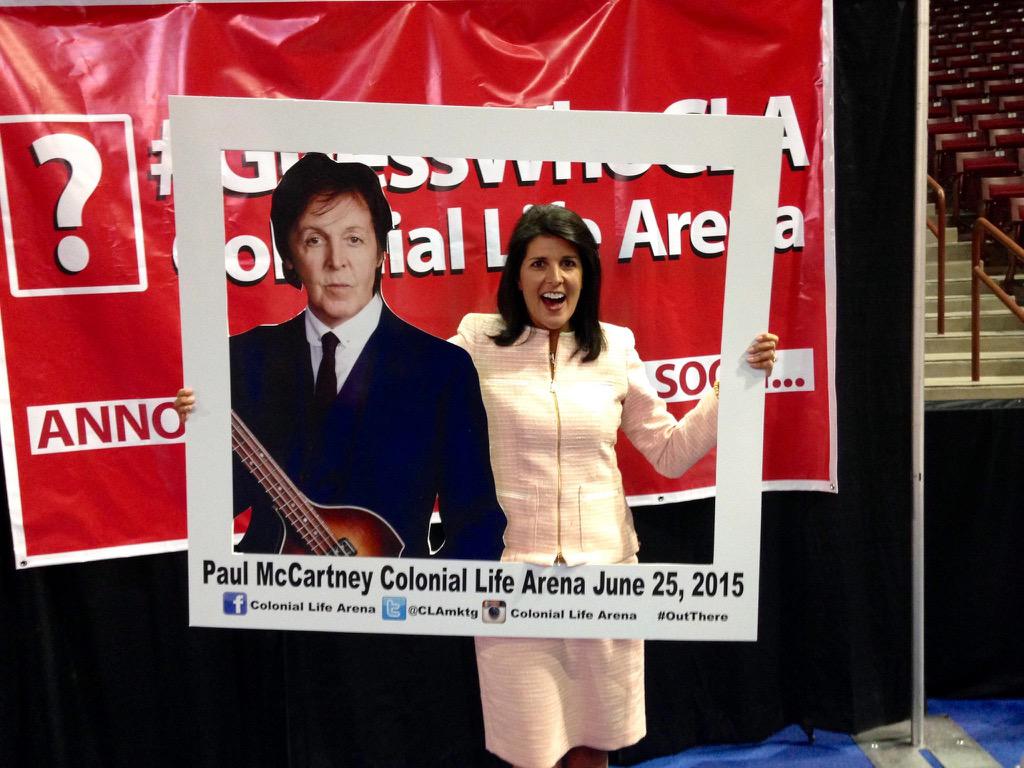

The letter, which the Israeli Embassy in London also sent to the two surviving Beatles, Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, and to the relatives of the late George Harrison, concluded with an invitation to McCartney and Starr to perform at a celebration of Israel’s 60th year of independence:

We are happy to invite you to perform in Israel’s independence celebrations and to fix a historical mistake from 1965 which prevented [Israeli] audiences from seeing a band which influenced a whole generation.

Palestinian groups around the world sent an open letter to the surviving Beatles and to the families of the deceased members of the band demanding that they honor the Palestinian cultural boycott of Israel and refuse to ever perform in Israel.

Paul McCartney bravely stood up to the hate groups, accepted Israel’s invitation, and, in celebration of Israel’s 60th Yom Ha’Atzmaut celebration, played Tel Aviv on September 25, 2008; a ticket from that historic concert is reproduced on this page.

(Years earlier McCartney’s post-Beatles band Wings had accepted an invitation to play Israel in 1979, and dates were secured in Tel Aviv for July or August. However, a strong disagreement between Wings promoter Harvey Goldsmith and the management of what was then the only hall in Tel Aviv that could host such rock concerts, forced cancellation of the proposed performances.)

When McCartney initially announced plans for his 2008 concert, he received numerous death threats. For example, terrorist spokesman Omar Bakri Muhammad publicly proclaimed that “Paul McCartney is the enemy of every Muslim…. If he values his life, Mr. McCartney must not come to Israel. He will not be safe there. The sacrificial operatives will be waiting for him.”

Israel, taking the threats very seriously, reportedly assigned a security detail team of some 5,000 officers and guards, including 20 elite Mossad agents, to protect him. McCartney would not be intimidated; as he told the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs: “I got death threats, but I have no intention of surrendering and I’m coming anyway.”

Speaking to Israeli reporters he said, “I’ve heard so many great things about Tel Aviv and Israel, but hearing is one thing and experiencing it yourself is another.” He acknowledged the country’s earlier Beatles controversy by noting that he was finally coming to Israel “forty-three years after being banned by the Israeli government” and he promised to give Israelis “the night they have been waiting decades for.”

And he did: in the face of continuing threats from Islamic and Palestinian leaders, McCartney became the first Beatle to play Israel, performing “Give Peace a Chance” and “Hey Jude,” among favorites, before some 40,000 fans in Ganei Yehoshua Park in Tel Aviv. He sprinkled his performance with various Hebrew phrases, including wishing the crowd a “shanah tovah” (Rosh Hashanah was five days later) and adding “ze mi’paam” (this one is from a long time ago) before singing “All My Loving.”

McCartney: "When I was told there was a concert in Tel Aviv I was looking forward to it. I've never been to Israel and the Beatles were banned originally, but I was conscious of the Jewish-Palestinian conflict."

McCartney: "When I was told there was a concert in Tel Aviv I was looking forward to it. I've never been to Israel and the Beatles were banned originally, but I was conscious of the Jewish-Palestinian conflict."

Before playing “My Love,” he declared “ze l’Linda,” dedicating the song to his late wife, Linda Eastman. (Many people do not know that Linda was Jewish, which means, of course, that McCartney’s children through her are Jewish as well.)

Though he carefully avoided political statements during the performance, McCartney met before the concert with Israelis from the One Voice Movement, whose mission is to empower Jews and Palestinians to push for peace and a two-state solution. He had also been scheduled to visit Ramallah, but that visit had to be cancelled for security reasons. Instead, Sir Paul visited Bethlehem where he stopped at a school for Palestinian children learning music.

* * * * *

Finally, I can’t write about the Beatles without recounting an amusing reminiscence of a Shabbat lunch I spent at my friend Ira’s table, circa 1970, which, I think, illustrates the band’s far-reaching impact on Jewish life and Jewish thinking.

The topic of conversation that afternoon was the reasons for the decline of contemporary morality and the decay of society and its institutions, as various positions were put forth spanning the breadth of political and philosophical thought. And then Ira’s elderly grandmother, a fine Jewish lady who, though she barely spoke English, was sharp as a tack, weighed in with a fervent opinion that essentially ended the discussion.

With fire in her eyes, fury in her nostrils, and the certainty of a person who will tolerate no dissent, she passionately spit out, in her thick Yiddish accent: “It’s those Beatles!”